ALAN PARADISE

.

July 07, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

ALAN PARADISE

.

July 07, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

As the automotive vernacular goes, the term “Pony Car” is fairly young. Many enthusiasts are under the impression it was first uttered shortly after the release of the ’65 Mustang, but automotive historians believe it surfaced a few years later when the Camaro and Firebird came onto the scene. Whatever your take, there is no denying the lasting effect the personal performance car has had on American automotive culture.

The fight for ’60s street supremacy among this class of car was fierce. The battle was pushed to a fever pitch not only on the boulevard but at the track as well. This was the golden age of showroom racing cars in America. Back in a day before OPEC, iPhones and the Designated Hitter, this country experienced real “stock car” racing, a time in America when race cars were gutted-out, hopped-up Sunday versions of what anyone could buy on Monday. The most popular versions were not the straight-line, quarter-mile machines, nor were they the mid-size hardtops of the Southern ovals. The most exciting, rock ’em sock ’em steel-bodied race car action was found on the Trans Am circuit.

Between 1966 and 1971, this style of stock car racing forced its drivers to swap paint at breakneck speeds on America’s most challenging road courses. It attracted the biggest names in motorsports, such as Penske, Donohue, Jones, Gurney, Titus and Shelby, to name a few. It developed an extremely loyal fan base that included those who were equally as loyal to NHRA drag racing and NASCAR.

Coming out of the ’70s, NASCAR clearly won the auto racing war. However, until 1972, Trans Am provided a battle. At the height of the Trans Am glory, from 1967 to 1971, the series was far more entertaining and competitive than any other form of racing.

NASCAR and SCCA Trans Am racing have as much in common as they do differences. While NASCAR is today’s most dominant form of motorsport, it could have just as easily become a second place series to Trans Am. It was, however, not to be. The primary reason for the fall from grace as the best American racing series in history is due to inner politics and over regulation. Like all good things, sooner or later its success became its demise.

The thrust of Trans Am racing happened due to the enormous success of the Ford Mustang and Chevrolet Camaro. Both cars sold so quickly that rival automakers reaped the benefit from the overspill with models such as the Firebird, Cougar, Falcon and Barracuda. Pony Car enthusiasts prepared their cars for use in sportsman-style track racing. As much of this activity was under the banner of the SCCA, the club wisely seized the opportunity and established classes with a National Championship category. The SCCA set up Group 2 cars under FIA Appendix 2. The amateur classes were based on displacement: A was 2000cc to 5000cc, B was 1300cc to 2000cc and D was less than 1000cc.

Trans Am officially began on a spring afternoon in March of 1966 at Florida’s Sebring Raceway. The day was filled with actual bumper-to-fender action as drivers in Mustangs, Darts and Barracudas manhandled their domestic sports coupes, fastbacks and hardtops around the various surfaces that made up the famed racing circuit. Ironically, the checkered flag cascaded over Austrian F-1 driver Jochen Rindt driving an Alfa GTA.

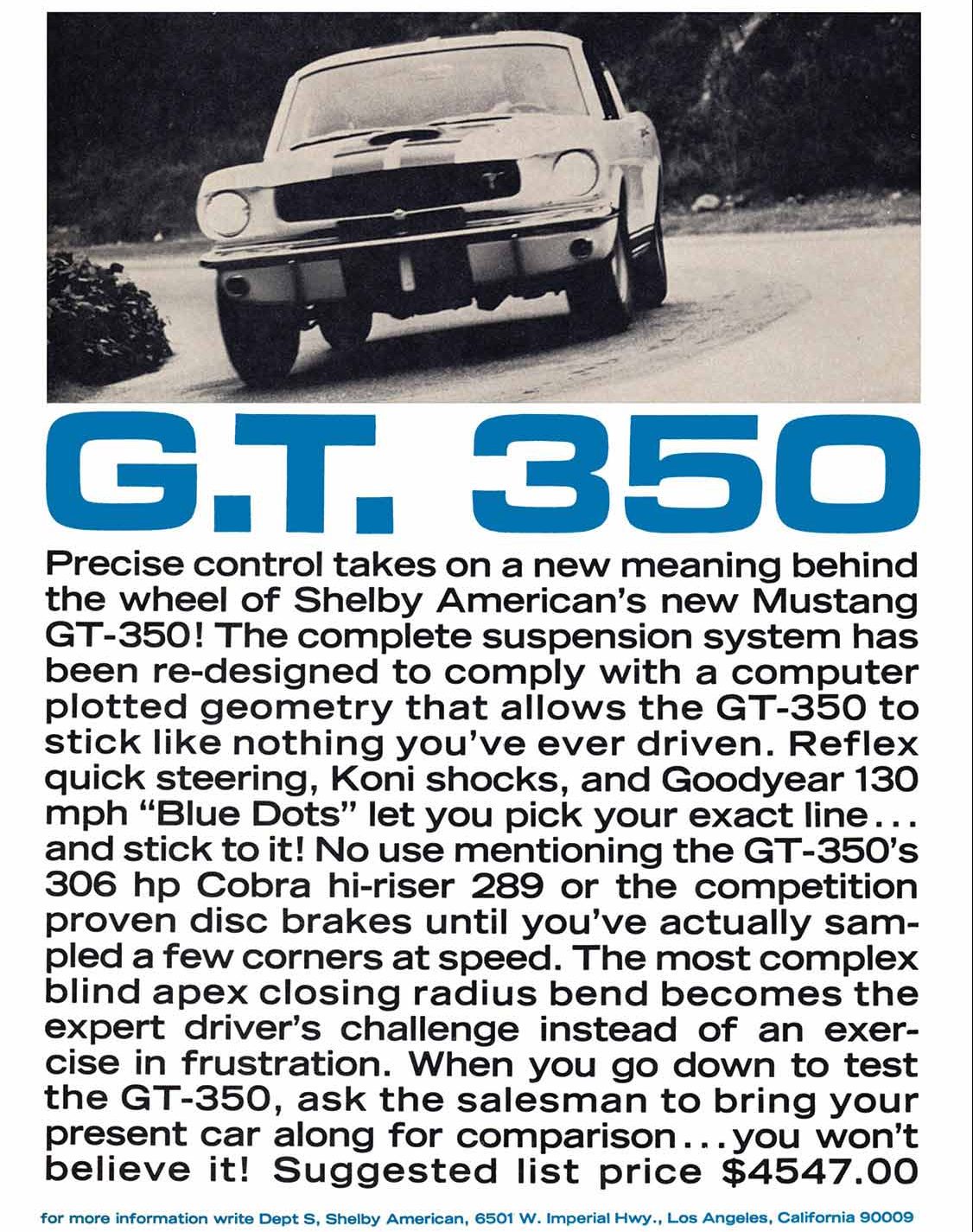

Throughout the following months, Shelby-built Ford Mustangs attempted to dominate the series on seven different tracks from Watkins Glen to Riverside. During the fight for the first championship, Ford and Chrysler battled for the points lead right up to the last two races. At Green Valley, Brad Booker and John McComb, driving a Shelby Group 2 Mustang, finished ahead of the Team Starfish Barracudas and Group 44 Dodge Darts for the win, tying the standings at 37 each for Chrysler and Ford. Going into the final race of the season at Riverside, Jerry Titus drove a Shelby Group 2 Mustang to victory handing Ford the first Trans Am manufacturer’s championship.

By 1968, the Ford vs. Chevy wars were in full effect. No place was this war more mightily fought than on the twists and turns of the Trans Am series.

In 1967, Titus won the driver’s championship and provided Ford its second manufacturer’s title. During that year, General Motors launched vehicles from its Chevrolet and Pontiac divisions that would force Ford and Chrysler to accelerate their racing efforts or be eliminated from contention.

Chevy’s new Camaro was designed to thwart the immense popularity of Ford’s Mustang. Pontiac’s Firebird, built on the same platform as the Camaro, championed the brand into the sales and racing wars. During that time, Chevrolet executive Vince Piggins understood the powerful youth market allure of Trans Am racing. As soon as the Camaro was ready to be track-proven, he committed Chevrolet to the series and personally took control of what came to be known as the Z28 project. The more formidable challenge was the engine displacement restriction. At the time Chevy’s performance small-block V-8 was 327 ci. SCCA rules were set at no greater than 305 ci. Chevrolet Racing engineers placed a crank from the old 283-cid engine into the 327 block. The result was a 302 template that would later be used to develop the famous 302 aluminum block engines for the 1967-69 Z28s. Chevy won only three races in 1967, but the data collected from competition was enough to make much bigger things happen for Chevy and Trans Am racing the following season.

By 1968, the Ford vs. Chevy wars were in full effect. No place was this war more mightily fought than on the twists and turns of the Trans Am series. With support from Chevrolet, Roger Penske armed his second year Z28 team with driver Mark Donohue, an emerging superstar of the auto-racing world. The Penske/ Donohue team proved nearly unbeatable in 1968, winning 10 of the series’ 13 races. Both the racing Z28 Camaros and Shelby-prepped Mustangs helped sell cars. Chevy sold over 235,000 Camaros (of which 7199 were Z/28 models), while Ford sold 317,000 Mustangs. The Mustang number is remarkable given that the first-generation body style had grown woefully weary.

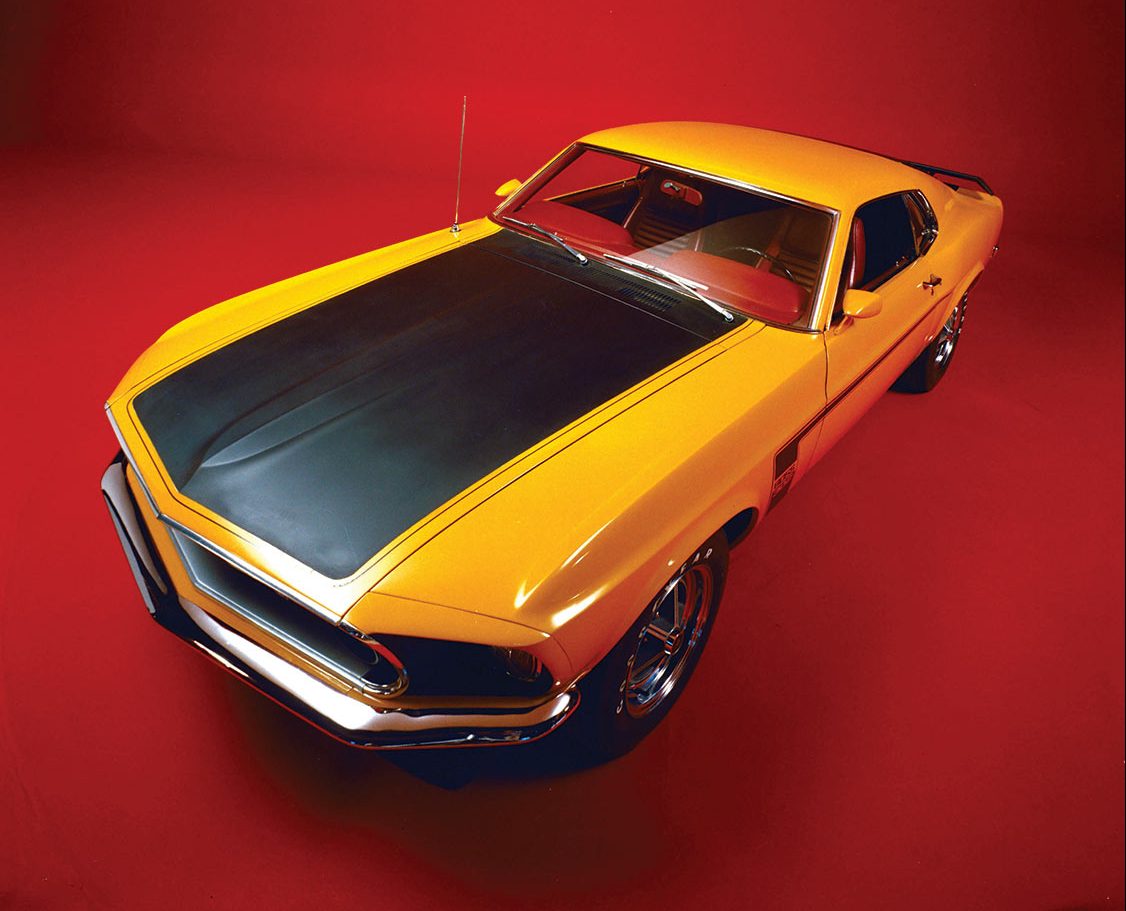

Chrysler, on the other hand, was swimming in mediocrity. At the beginning of the 1969 Trans Am season, the Mustang Boss 302 was unveiled and the Penske Camaros were being fitted with even more horsepower and handling setups, both on the track and in street trim. Plymouth was still saddled with the Barracuda, while Dodge enthusiasts had only the brick-shaped Dart to cheer for. It had become all too clear that before long both Chrysler brands would need to make serious changes.

In the meantime, despite the new engineering, body styling and a 302 power plant, Ford failed to catch up to Chevy on the track. Once again, Mark Donohue ran away with the driver’s title and Chevrolet took the factory bragging rights. On the street, however, the story was far more encouraging. The new Mustang sold extremely well with the Boss and Mach-1 being the halo models.

Many significant performance tricks that later found their way to the street started by way of Trans Am racing efforts.

Major changes in teams and rules made the 1970 Trans Am campaign a true knockdown, drag-out fight from beginning to end. The big news was that the cubic inch restrictions of a maximum of 305 no longer applied to the street versions. Now the redesigned Z28 could be fitted with the LT-1 350 for showroom models and the new Dodge Challenger and Plymouth ’Cuda would offer the 340. To make matters even more complicated, American Motors was in the game with the Javelin.

What made it possible for AMC to enter the field was the signing of Roger Penske. AMC was desperate for a fraction of the brand recognition lavished on Mustang and Camaro. In fact, AMC would have been happy to be as well respected as the Mercury Cougar (which pulled out of Trans Am after the 1969 season). The Javelin was AMC’s only true potential racing platform. The problem was that the smallest production V-8 engine offered in the 1970 performance version of the Rambler-like Pony Car was 348 ci. The new street restrictions made it possible for AMC to compete for retail sales while stroking the smaller 290 to achieve a 305-ci race engine.

For the next three model years, Pony Cars were the hot ticket. Sales soared and model variants were plentiful. The effect of Trans Am racing on the ideal that what won on Sunday sold on Monday was more prolific than what was happening in traditional stock car racing and on a par with NHRA Super Stock and Funny Car classes. Performance-equipped Camaro Z28, Mustang Boss 302, ’Cuda AAR, Challenger T/A and Javelin Donohue Edition models had become dream machines for a new generation of enthusiasts.

As a testament to the powerful connection between the showroom and the track, the 1970 Trans Am season was the pinnacle of American sport coupe racing. Nearly every team had big name drivers: Dan Gurney, Sam Posey, Parnelli Jones, Mark Donohue, George Follmer, Swede Savage, Peter Revson and Jerry Titus (who was killed during the season in a track mishap). Titus’ unfortunate death threw a blanket over the Pontiac team, not to mention sadness over the entire season.

Many significant performance tricks that later found their way to the street started by way of Trans Am racing efforts. Ford race engineers discovered that the heads of the 351 Cleveland engine added much needed volume and breathing capabilities to the tunnel-port 302 block. This improved throttle response as well as torque. After experimenting with this combination in 1969, the exact formula was worked into the engine. This, along with suspension changes, provided the Boss Mustangs with the power and handling to run bumper-to-bumper with the new Z28s as well as the high-dollar Javelins and pesky Challengers and ’Cudas.

It was a monster season as Ford Boss Mustangs were running side by side with the Penske/Donohue Javelin. By season’s end, Parnelli Jones squeezed out a one-point driver’s championship over Donahue. However, that was the end of the party. In 1971 near all factory support was dropped. Gone were the ’Cudas and Challengers. Chevrolet severely cut back its dollar investment, and Ford yanked its support as well. Conversely, NASCAR popularity began to take flight with new television contracts and factory-supported racing efforts. From 1971 to 1974, the series continued to slide in a rapid downhill fashion. The low point came in 1974 when only three races were run.

Although the racing was no longer robust and popularity fell off faster than the horsepower ratings of the decompressed, smog-pump engines in the street cars, the effects of the Trans Am era on the enthusiasts’ market continued to be felt for decades to come. EPA and auto insurance companies all but put an end to nearly 10 years of unrestricted street performance. While nameplates like Road Runner, GTX, Challenger, Barracuda, Torino and GTO remained on the scene for a few more years, all were just a shadow of their former selves. What remained as the halo of performance were the three most popular Pony Cars of the Trans Am era: Camaro, Mustang and Firebird.

As the ’70s slipped into the darkness of overregulation and the economic woes of the early ’80s, the fate of the Trans Am heroes also diminished. The Mustang went out of production in favor of the Pinto Plus Mustang II, a car Lee Iacocca dubbed “the mini Pony Car.” Adding insult to injury, the hottest Camaro (still sporting Z28 badges) was reduced to a measly 170-hp. The Firebird Trans Am, even with the severely detuned 455-cid engine, could only muster 200-hp. The late ’70s and early ’80s were indeed a dark time in an automotive America. It seemed that the most exciting production-based track action the country had ever seen was gone and forgotten. The accomplishments of great drivers like Gurney, Jones, Titus, Donohue, Savage and Revson only echoed in our distant memories.

In new car showrooms, only the new Fox Chassis Mustang and Camaro IROC-Z brought hope to a once robust performance market. An entire generation of future automotive enthusiasts was lost in the darkness. If not for the Trans Am relics of Mustang, Camaro and Firebird (and to some extent the custom truck scene), there might not have been gasoline dreams for anyone born after 1975.

However, a slight flicker of light inspired by Trans Am racing survived. When the Mustang GT brought the nameplate back to respectability, it forced Chevy and Pontiac to step up their game as well. Ford’s television and print ads touted that “The Boss is Back” to the roar of a factory performance car with a four-barrel carburetor, a five-speed gearbox and dual exhaust. The Camaro and Firebird matched Ford’s efforts as all jumped back into racing in a much bigger way. IMSA and SCCA events were populated with track versions of the Mustang, Camaro and Firebird.

In 1993, everything took a huge step forward by taking a long look into the past. The new fourth gen Camaro debuted in the summer of 1992, and the Firebird followed a month later. Ford’s reply was the SN-95 Mustang one year later. The three holdovers from the Trans Am era of the late ’60s and early ’70s were back in full competition force, in the showroom, on the street and at the track.

Suddenly, the old days had returned. Racing, once again, became an important part of marketing. Horsepower increased as new technologies allowed for far better engine control and reduced emissions. The old adage “you are what you drive” became a vital part of the ownership image, and Camaro, Mustang and Firebird were viewed as just a notch below Corvette.

Then, the winds of change again put a halt to the progress. As the economy slowed at the dawn of a new century, General Motors found that factory capacity levels were out of proportion to sales volume. Interest in Camaro and Firebird had slowed in favor of smaller, import roadsters. The Boisbriand plant in Canada, where both the Camaro and Firebird were produced, had become a financial drain on a once mighty General Motors. With the impending demise of certain GM brands, such as Oldsmobile and Saab, as well as talk of ending the Saturn, Hummer and even the Pontiac brands, there was little room for a halo sports coupe. It was decided that after 35 consecutive years of production, the Camaro and Firebird would be retired. In August of 2002, the final Camaro rolled off the production line. Shortly thereafter the assembly plant was closed. Ford had won the Pony Car war of attrition.

However, you can’t keep a good thing down. Just seven years after the exit of the Camaro, it came back to a market revived by the old Trans Am images of Mustang versus Challenger versus Camaro. All three nameplates were back in the showroom competing for new muscle car buyers.

The Trans Am effect had not only made the famous models relevant again, it severely spiked the values of consumer versions of the original Pony Car that ran on America’s premiere road courses. Auction prices of 1967-69 Camaros have reached new heights. Likewise, the desire for 1970-71 ’Cuda and Challenger models have put them into the upper echelon of American automotive royalty alongside the original Shelby Mustang GT-350.

This type of far-reaching influence never entered the minds of those who conceived the original Trans Am racing series. It was never a thought that the fender-banging, paint-swapping and bumper-car action that was early Trans Am would have a lasting effect on the automotive industry and the enthusiasts that feed it. But, it has and can once again be purchased at dealers flying the Blue Oval, Bow Tie or Pentastar flag.

Share Link