Rod Short Rod

.

July 01, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Rod Short Rod

.

July 01, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

For those who love the nostalgia era of drag racing, Ron Rinauro’s California-based ’55 Chevy 210 Club coupe can be found in the yellowed, dog-eared pages of a well-known magazine dating back to 1966. Aptly named Blown Hell, this altered-wheelbase shoebox Chevy was a regular at tracks like Fremont and Half Moon Bay many years ago. Back then, the car ran a 292-cid small-block with a GMC 6-71 blower, Hilborn fuel injection and a Vertex magneto on 10% nitro. Using a TorqueFlite transmission, the best numbers for Rinauro’s combination was a very respectable 9.73 at 146 mph.

While these cars were (for the most part) gone, they were never really forgotten. When they are rediscovered, a flood of emotion usually follows.

Back in the day, teenager Jerry James was just one of many budding performance geeks sitting in the rickety wooden stands of those fabled raceways. As time passed, James went on to grow up and served our county in Vietnam aboard the USS Ranger. One of the things that helped him through those times was that he never quite shook the memory of seeing cars like Blown Hell scream down the quarter-mile. After mustering out of the Navy in 1970, he went on to refine his mechanical skills racing stock cars and hydroplanes. Then, out of the blue, he was presented with an opportunity to recreate that old Chevy Gasser that was so fondly etched in his memory bank.

To hasten weight transfer off the line, altering a vehicle’s stock wheelbase was done early on in drag racing. This is best remembered by the factory Super Stock wars of the mid-’60s. Factory-backed Dodge and Plymouth altered wheelbase (AWB) cars became widely known first and were quickly followed by Ford and Mercury as the tales of their door-to-door battles filled the imaginations of baby boomers. AWB Chevrolets were seldom seen because of the factory ban on racing, although a number of independents, including “Jungle” Jim Liberman, successfully ran such cars.

The AWB cars were the jumping off point for what became the Funny Car. It was during the transition point where innovators like Jack Chrisman and Tom “the Mongoose” McEwen changed the entire direction of drag racing. With the overwhelming success of the Funny Car, AWB and Gassers faded from the scene.

While these cars were (for the most part) gone, they were never really forgotten. When they are rediscovered, a flood of emotion usually follows. “I came across the car at a friend’s shop in 2008,” James remembers. “It was pretty ragged. It had been run as a Gasser in a previous life and the body was just sitting on a different frame. It wasn’t even bolted on. It had a fiberglass nose, but it needed replacing and it needed new quarters. It had no doors, glass or interior and the floors were all rotted away. Really, turning it into a race car was the only thing to do.” That’s just what James did.

James hand built the chassis using an S&W Race Cars mild steel back-half kit grafted to the original frame. The rear axle, which was moved up 20 inches, was the anchor point for a Dana 60 differential with Strange spool/axles, Richmond 4.56:1 gears and Wilwood brakes.

All that’s needed is exposure to these special, purpose-built machines to shift the tide and bring in a new generation of enthusiasts. It is a strategy the NHRA is diligently working to figure out.

The front suspension was fitted with a semi-elliptical straight axle kit using Chevy spindles and disc brakes. Afco coil-over shocks were installed on both the front and rear. Classic American Racing wheels up front lead the charge forward while wide Weld wheels shod in 14×31 Goodyear slicks launch the car off the line.

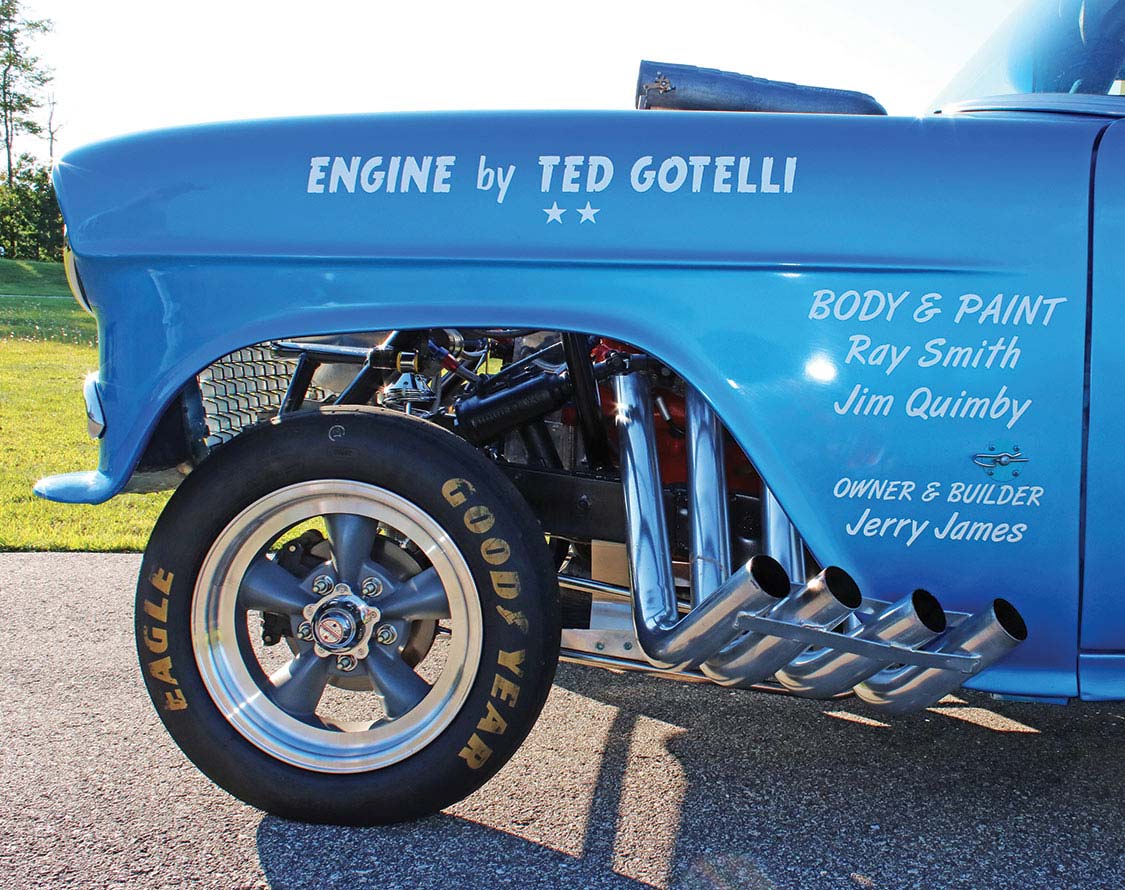

James knew that the days of running a bored-out 283 Mouse were long in the past. Inside the revived and reinforced engine bay resides a 427 Rat motor combination based off of a stock deck height Merlin block. The beefy bottom end consists of an Eagle crank with Scat H-beam rods and Keith Black 11.6:1 forged pistons. An 8-quart Ed Hamburger oil pan filled with Valvoline 50-weight racing oil covers the bottom-to-top lubrication. Out-of-the-box Brodix BB-2 X aluminum heads, a Blower Drive Service intake, Mooneyham 8-71 blower and a Hilborn fuel-injection setup makes up the eye-catching induction system. Jones runs methanol that is fed by an Enderle 110 pump from an 8-gallon tank. One visible departure from photos of the original car are the zoomie-style headers that were fabricated from a Smiley’s Custom Headers kit.

Backing up the engine is a Ted Mazzotta-built Powerglide using an ATI 5,000 stall converter. When launching the car off the line at 2,000 rpm, James has recorded a personal best time of 9.17 seconds at 141 mph. Not too shabby for a car weighing in at 3,300 pounds.

“A lot of people like to look, ask questions and take pictures of the car,” James said about being at the track. “My friends were all for it and I tried to build it as close to original as I could, but some of them didn’t understand why I was altering the wheelbase. None of them had ever seen anything like it, which is one of the reasons why I built the car in the first place.”

“Nostalgia drag racing is popular right now, but you don’t see many young people driving nostalgia cars; it’s mainly white-haired guys,” he continued. “It has me worried about its future.” All that’s needed is exposure to these special, purpose-built machines to shift the tide and bring in a new generation of enthusiasts. It is a strategy the NHRA is diligently working to figure out.

Of course, any history buff will tell you that discovering relics of the past is exactly what’s needed to keep alive the rich history of drag racing. There are hundreds, perhaps even thousands of aging Gassers, Altereds and AF/X cars hiding in places unknown. It is vital that these links to the past be resurrected and revived. It is even more important for the old guard to mentor the next generation on the thrill of building and driving these special vehicles. With the work we’ve seen from Jerry James put into this vintage racer, the future of old school drag racing shines a little bit brighter.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link