ALAN PARADISE

.

February 05, 2023

.

All Feature Vehicles

ALAN PARADISE

.

February 05, 2023

.

All Feature Vehicles

It was just another bleak late winter’s day in Detroit. The year was 1927 and a brash Californian had come to General Motors to bring style to an otherwise utilitarian automotive industry. Shorty thereafter, the 33-year-old would forever change the way the world felt about owning a car.

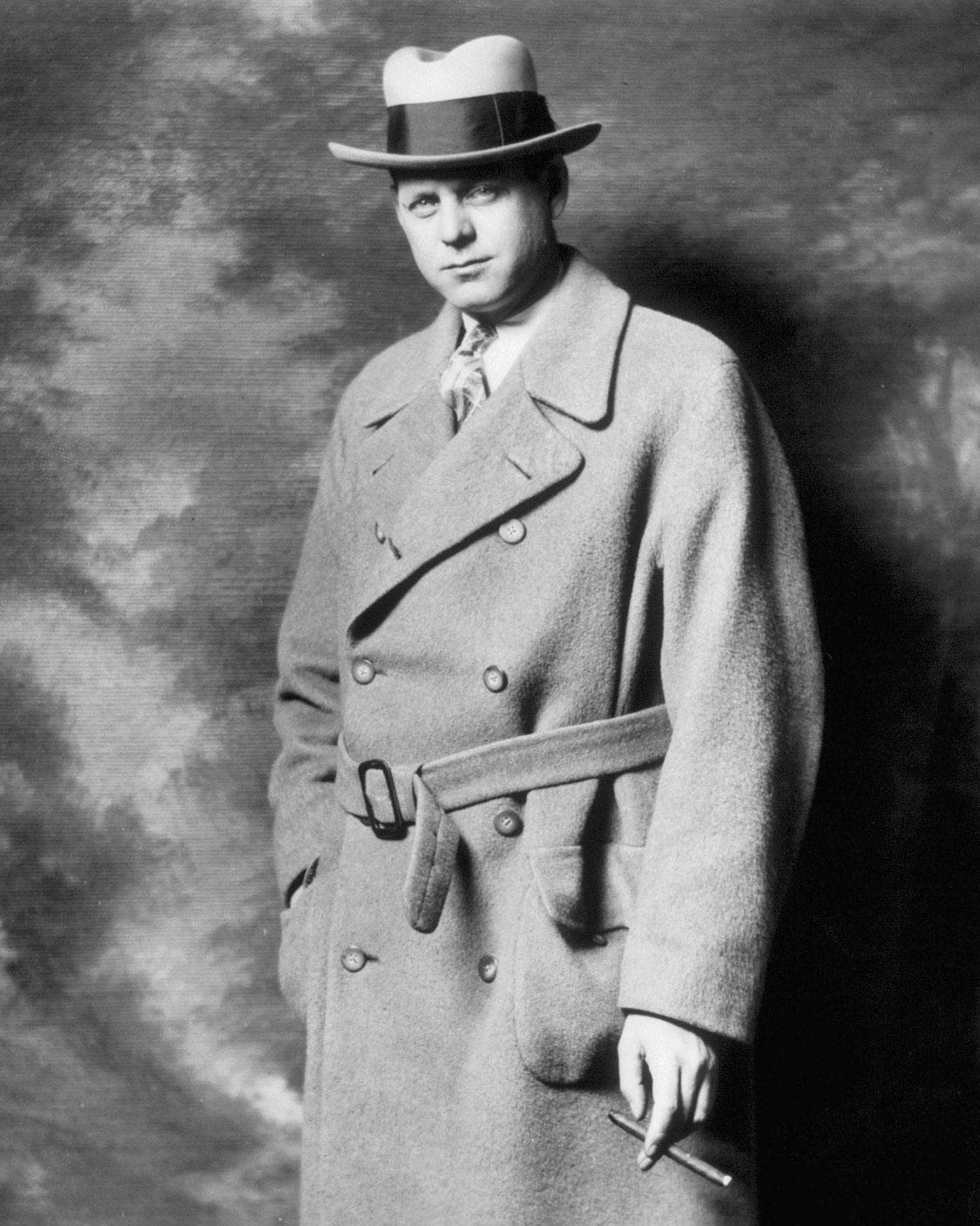

Perhaps second only to Henry Ford, no one in the American automotive history is as important as Harley J. Earl. His talents and vision literally shaped the entire automotive landscape. While Ford created the assembly line approach for a nation on the move, Earl brought form and beauty to mechanical function. He developed a formula that demanded General Motors give equal weight to design, and in the process developed the idea of what the automobile said about its owner’s personal image. Within a few model years, Earl’s influence had transformed the car from something you needed to have into something you deeply wanted.

Earl was a giant of a man, standing 6-foot 4 inches and always impeccably dressed. He came from Hollywood and was the coach designer to the stars. Everyone from Tom Mix to Fatty Arbuckle drove down Sunset Boulevard in Cadillac chassis covered with Harley Earl custommade bodies. Not far removed from his college days at Stanford University, he had a unique vision and understanding for turning four-wheel machinery into moving pieces of art.

Earl’s talent and confident attitude attracted the attention of Alfred and Lawrence Fisher. If those names aren’t familiar, you need look no further than the kick panels of most any classic GM car. Look for the emblem of a carriage with the words “Body by Fisher” around it. Shortly thereafter Earl became a consultant to the Fisher Brothers until Alfred Sloan took over as chairman of General Motors. Sloan promptly persuaded Earl to become GM’s first head of styling. This wasn’t just a first for GM, it was also a first for the entire automotive industry.

Earl’s first design was the LaSalle, a stylish roadster that bridged the gap between the Cadillac and Buick brands. It was a sleek, sophisticated shape that instantly established the new nameplate as a car for the then upwardly mobile generation. More than 50,000 LaSalles were sold in the next three years.

The Great Depression had a major affect on the auto industry, but Earl instinctively knew that style and self-image were always going to be in fashion. He also understood that dreams and the hope for better days ahead were powerful forces of the human spirit.

In the middle of America’s most downtrodden time, Earl convinced GM’s board of directors to tap into a vision of the future. This was done with the idea of dream cars. In the spring of 1938, GM released the Buick Y-Job, the first dream car. The term “dream car” would later evolve into the concept car. However, in the middle of the Great Depression and with the unrest in Europe lapping against the shores of the United States, Earl realized that the public idea of a dream car was something that would spark great interest. He was spot on.

The Y-Job was exactly what dreams were made of, with such progressive styling features and a body void of running boards, low split windshield, hideaway headlights, flush-mounted door handles and trim that made the car look like it was moving while standing still. When the Y-Job was introduced to the public it vaulted GM into the role of the automaker of the future, the exact place Earl was aiming for.

The Y-Job was more than just an exercise in styling; it was a fully functioning car. After it returned as the main attraction of GM’s Motorama tour, it became Earl’s personal mode of transportation.

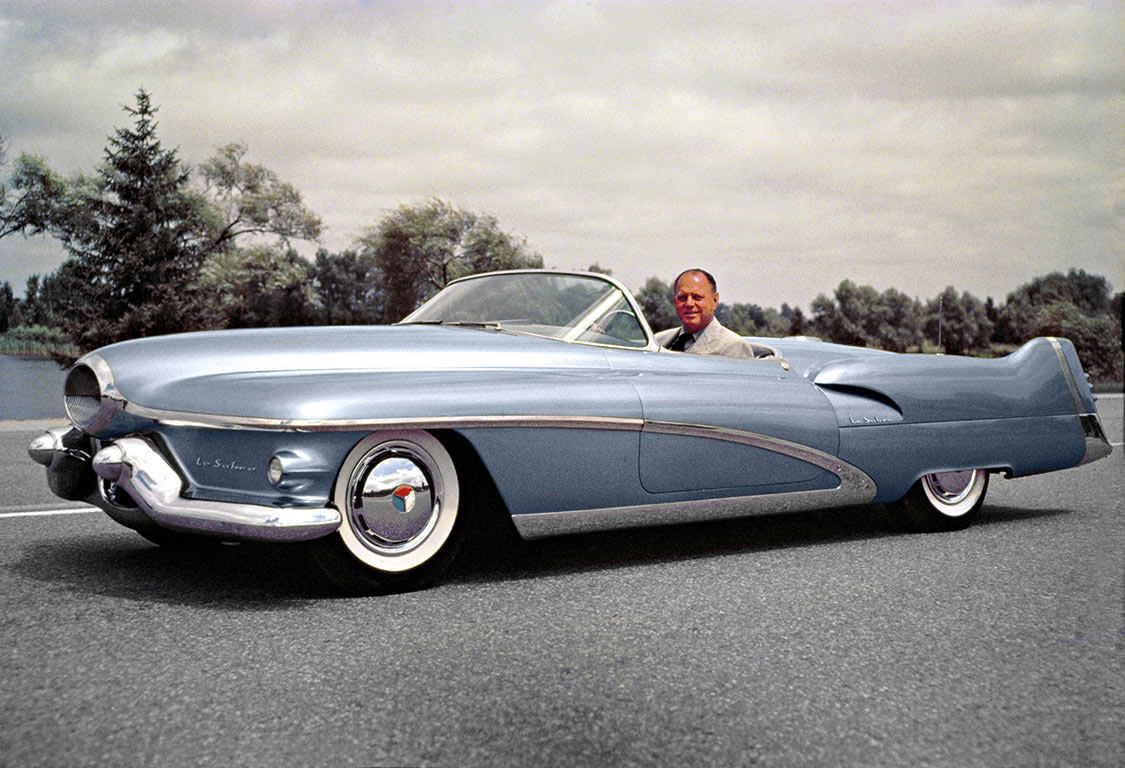

When the United States entered World War II, GM put the building of dream cars on hold. Earl took his styling teams (which now included Bill Mitchell) into the war effort designing a multitude of ideas. One of which was the concept and uses of camouflage. Earl and team helped develop patterns and variants that would better serve the Allied forces. When the war was winding down, GM prepared to convert its mighty manufacturing machine back to the business of personal and trade transportation. Earl was directly at the heart of these efforts. In 1946, all of the major automakers put the tooling for the last production models back on line. This was a stopgap measure before a new generation of cars and trucks could be styled and engineered. Once again, GM led the styling revolution with the 1948 Oldsmobile Futurama, followed a model year later with the 1949 Buick Roadmaster, Cadillac Sixty-Two, Chevrolet Styleline and Pontiac Chieftain. These were all styled radically different from all pre-war cars with one notable exception, the Buick Y-Job. The dream had now become reality and Earl, the father of the dream car, had refired the flame with the LeSabre, a space-aged styled concept car that was so far ahead of the curve that no one outside of Earl fathomed the impact it would have as it featured the industry’s most memorable and significant exterior styling feature, the tailfin.

The tailfin was inspired by Earl’s visit to a Michigan Air Force base several years earlier. As he wrote in his memoirs, “When I saw those two rudders sticking up, it gave me a postwar idea. When it was introduced, it started a war in the corporation.”

The LeSabre headlined the 1950 Motorama. The reaction to the two-seater was even more overwhelming than that of the Y-Job. While some of the design elements of the LeSabre were never put into production, the tailfin started to emerge from the sheet metal of 1952 Cadillac, Buick and Pontiac models.

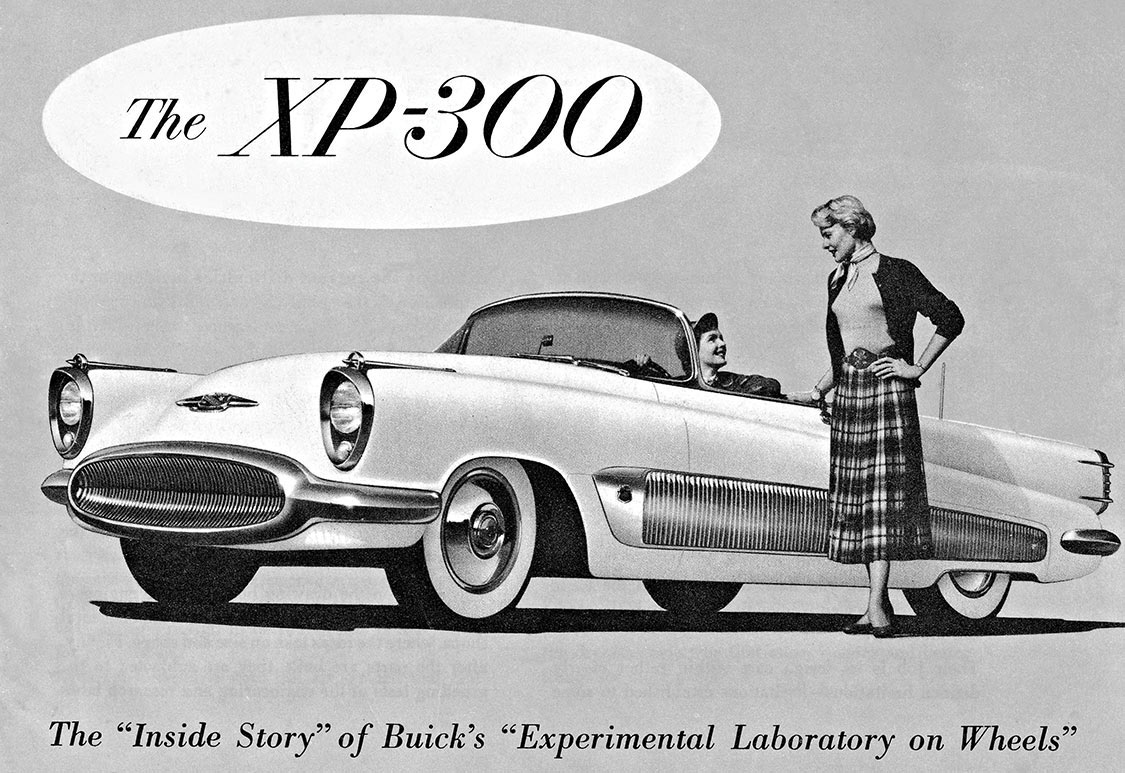

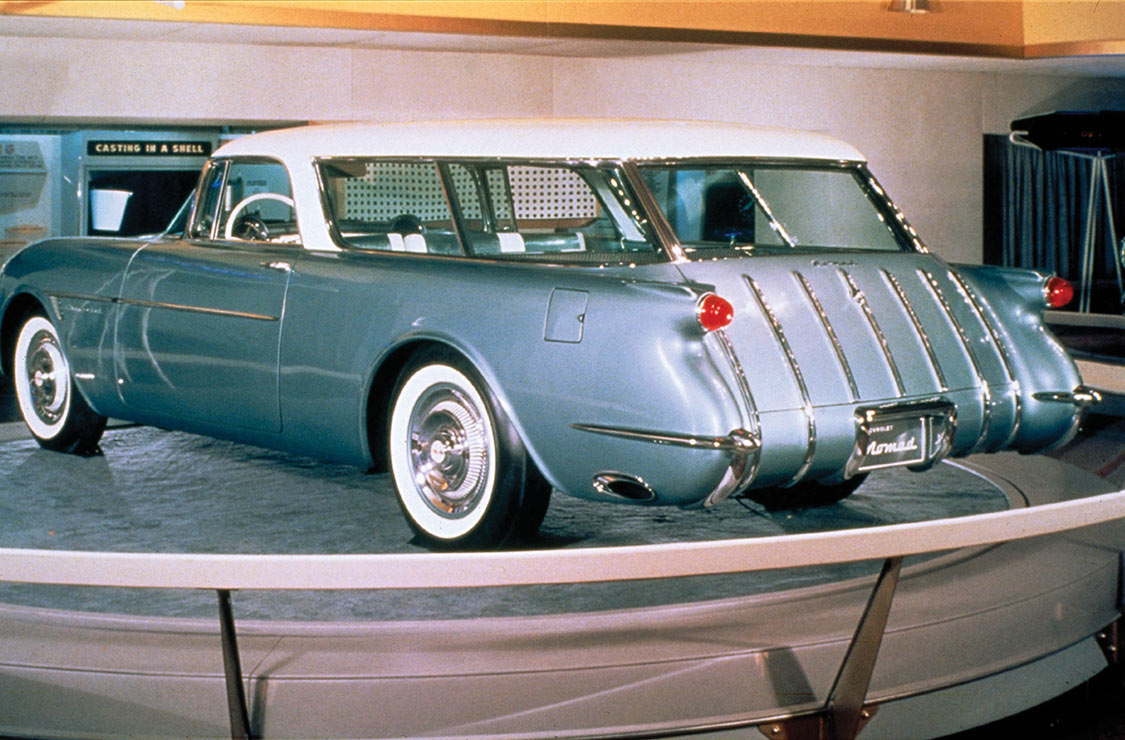

The success of the LeSabre allowed Earl to expand his reach of the concept car. In the next three Motorama seasons, Earl and team created concept cars that would all become production cars and each transformed their brands as well as the industry. First came another two-seat roadster for Chevrolet named Corvette. Then came the Cadillac Eldorado Brougham, followed by another Chevrolet, the Nomad.

The ’50s was an extremely formative era. American industry led the world, cultural standards were in transition and global economics were beginning to rebound. At the heart of it all was General Motors, the largest corporation on Earth. Earl was the driving force behind the popularity of all GM efforts. Under his leadership, GM introduced tailfins, aerodynamic testing, chrome-plated body trim, fender jets, portholes, the first color and fabric studio, created two- and tri-tone paint palettes and made seatbelts standard equipment.

GM’s styling studios were in full command of the auto giant. During this time market share grew and competitors vanished. Following World War II, there were 10 significant American automakers. By 1963, there were four. The decline in competitors has been directly attributed to the prowess and vision of Earl and the industry dominance of General Motors. Using forward planning and cutting-edge styling mixed with the ability to engineer and manufacture styling that changed each model year simply overwhelmed lesser automakers as they ran ragged just to try and keep pace.

At the height of the ’50s styling revolution, General Motors had more than 1,100 designers working under Earl. This didn’t include the 100 more at Frigidaire. This forced Ford and Chrysler to create styling divisions. In an effort to compete, the two rivals hired designers trained under Earl.

There was a pyramid of power to which everyone strictly adhered. For the most part, Earl didn’t have direct or daily contact with the vast majority of the designers in the various studios. Instead, he would meet and communicate with the studio heads that would then move the messages along. He felt this improved loyalty to each rung in the ladder.

The exception to this rule came via an innovation that literally changed the culture of the industry. In the early ’50s, Earl set out to find the brightest, most talented women designers in the country. The search covered leading universities, design colleges and art studios. By 1953, he had assembled talent that would bring a new perspective to the otherwise male-dominated auto industry. This was a stroke of genius because public purchasing decisions were becoming more inclusive, giving women far more buying power than ever before. Earl saw this coming and, like always, stayed several steps ahead of his competition.

Because Earl gave us so many iconic design elements such as wraparound windshields, quad headlights, integrated exhaust ports and bullet taillights, he’s often overlooked for being miles ahead of the rest of the Detroit pack in safety and engineering. In 1934, he designed and engineered all-steel roofs, an innovation that saved countless lives as one of the most significant pre-war safety features. He was the first man to advocate for computer integration. He pushed GM to be the first to use crash-test dummies to gather potential injury data and helped usher in the use of seatbelts and anti-lock brakes.

Of all of the automobiles that rolled off GM assembly lines during the Earl era, perhaps none are more iconic that the 1955-57 Chevrolets. Earl worked directly with Chevrolet studio head Clare MacKichan on the landmark design. Earl pushed MacKichan to “go all the way, then back off.” The high, dipping beltline, lower roofline, wraparound windshield, eggcrate grille and aerodynamic trim leapt off the page and right into production. When mated with the new OHV V-8 that Chevrolet Chairman Ed Cole and engineer Harry Barr had been developing for the past few years, the result was a once-in-a-lifetime creation, a blue-sky development that altered the course of the industry. Throughout the next two model years the styling was refined and gently advanced. At the same time so was the size and power of the new engine. Together they created the standard by which all new cars would be judged for the next decade.

Perhaps no car in the parade of Earl’s achievements is more significant that the Chevrolet Corvette. Most have been led to believe that Bill Mitchell and Zora Duntov were the masterminds behind the first true American sports car. In truth, both of those great men were Earl appendages. The Corvette was an Earl concept and reality from day one. Mitchell shared the passion and was a big part of the process from the original clay model to overseeing the first concept car. Later Earl and Mitchell pushed to create concept versions for the brands that passed on the idea of the Corvette. Those efforts resulted in the 1954 Pontiac Bonneville and the 1954 Buick Wildcat concept cars. But, by that point, even the Corvette was in jeopardy of remaining part of the Chevrolet line.

When Ford introduced the more refined and higher priced Thunderbird, GM had no intention of conceding defeat to its Dearborn rival. It gave Earl the backing to build a real sportsmen’s car. It was at this point that Mitchell took more of a day-today interest in the Corvette. They brought in Duntov to create the first dream team of styling and performance. Each year the Corvette progressed until it became the halo nameplate of the entire American automobile landscape.

Everything that Earl did, from the late ’20s until his retirement in 1959 caused a ripple effect with GM and a tidal wave with its competitors. He did more to advance the art of styling than anyone before or since. Nearly 50 years have gone by since his passing (1969), and for the most part there is very little known about his accomplishments. This begs the question of why doesn’t GM embrace his legacy? For a short time there was an attempt to bring back the ghost of Earl in a series of Buick television commercials. However, those 30- and 60-second spots fell far short of depicting the magnitude of what this man did for the automobile. It was as if General Motors had abandoned his remarkable deeds and now wanted to somehow capitalize on his memory.

For the true automotive buff, Earl is an icon of styling. His importance has not been totally lost. The winner of the Daytona 500 is awarded the Harley Earl trophy that features the famous Firebird I concept car. His memory also lives through every tailfin, porthole, chrome bumper, two-tone paint scheme and curved windshield. When you see a concept car, regardless of its maker or country of origin, think of Harley Earl, he was the man that made our automotive dreams come to life.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link