REUBEN BOLIEU

.

April 24, 2024

.

Tread

REUBEN BOLIEU

.

April 24, 2024

.

Tread

In the December 2022 issue of Knives Illustrated, we journeyed together through the Philippines in search of bolo knives. That was only the beginning of my quest to find authentic, hand-forged blades of Southeast Asia. More countries and more adventures were ahead of me. It was a work in progress, but until then I hadn’t seen many forges in working operation up close and personal.

My first trip to Thailand was behind a camera in awe of what I consider to be the greatest subjects for a photographer. Strolling through the marketplaces in Thailand, I couldn’t help but notice the many different blades being used to process chicken, fruit, and food in the many street restaurants. After a few days, I soon learned of a village about a five-hour drive from where I was staying in Pattaya, Thailand.

This place was called Ayutthaya, once officially known as Siam, which was one of the most ancient cities in Asia. Ayutthaya was once regarded as the strongest power in mainland Southeast Asia, full of history and the most amazing temples. Ayutthaya is now considered somewhat of a tourist stop or a day trip out of Bangkok. However, I was there not only to see the temples, but to visit the legendary knife village of Aranyik. Wiai Roeycharoen Knife Shop is the name of the shop and forge I visited and where I bought a few big chopping blades.

The entire village is part of a program called OTOP (One Tambon One Project). The program aims to support the unique locally made and marketed products of each Thai tambon (sub-district). Thailand’s OTOP program encourages many village communities to improve local product quality and marketing, selecting one superior product from each tambon to receive formal branding as a “starred OTOP product.” This provides a local and international stage for the promotion of these products.

“THE THAI E-NEP IS KIND OF THE CALLING CARD OF THAI BLADES, OFTEN REPRODUCED BY PRODUCTION COMPANIES AS THE BIG CHOPPING KNIFE OF THAILAND.”

Being at the forge was akin to those of the Philippines, but there were some major differences. For one, the blade shapes were different, and the fuel used in the forging process was different. They used charcoal for some projects, but they also used bamboo, which produces an excellent form of charcoal that generates the extreme heat required to shape the steel used to forge Aranyik blades.

The two styles of blades were the E-Nep and E-Toh. Both blades are very traditional blade shapes of Thailand and are easy to get from various markets in the surrounding areas. Also, wouldn’t you know it? They chose 5160 leaf-spring steel for their tools.

The one forge in Aranyik that I visited had a very small anvil for pounding out blades. It was more like a squared chunk of metal sticking out of the ground. The hammers were squared pieces of metal attached to small, dry bamboo wood via a leather strap. These were not regular commercial hammers, but who am I to say? Their work is amazing regardless of their chosen work tools.

They also made these knives in the style of the one-piece tube handle design seen in the Philippines and Vietnam. Like the mountain province bolos of the Philippines, these were strong in construction because of the nature of the continuous piece of steel. However, none of the blades I came across in Thailand came with a nicely woven rattan handle like those found in the Philippines. That doesn’t mean that they had less function, just that the grip was different. If one was to sweat, it may cause the knife to slip out, but that didn’t seem to happen on my watch.

“THE PARANG IS THE MACHETE DESIGN OF MALAYSIA. I WOULD HAVE TO SAY IT IS THE MOST MIMICKED CHOPPING BLADE DESIGN IN THE MODERN CUTLERY INDUSTRY…”

These blades are meant for chopping up coconuts and firewood. All featured a weight-forward balance and super-scary sharp cutting edge. The Thai E-Nep is kind of the calling card of Thai blades, often reproduced by production companies as the big chopping knife of Thailand. It has a kukri (blade from Nepal) look to it, but with a full tang and hardwood scales. A full tang extends the full length of the grip portion of a handle, versus a partial tang or stick tang, which does not.

Perhaps the most common design in full-tang knives is when the handle is cut in the tang’s shape and the handle scales are then fastened to the tang by using pins, screws, bolts, and epoxy. They left the tang exposed along the belly, butt, and spine of the handle, extending both the full length and width of the handle. Needless to say, it makes for a much stronger, robust chopper in which the handle cannot come loose like with stick tangs.

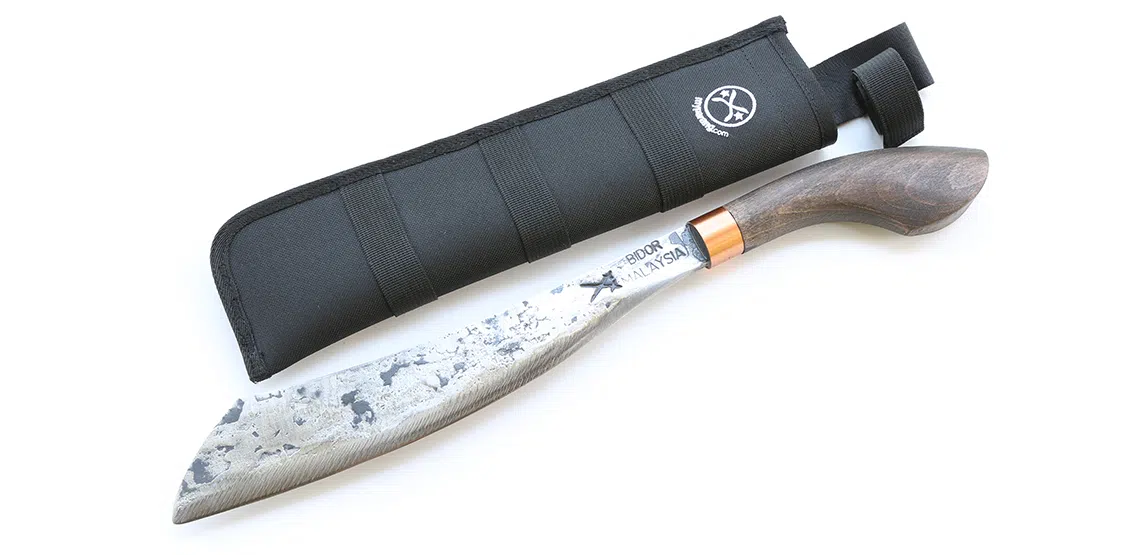

The parang is the machete design of Malaysia. I would have to say it is the most mimicked chopping blade design in the modern cutlery industry, and sadly, most designs calling themselves parangs are a far cry from a real parang!

It was in Penang where I met with my friend Ahmad Nadir, who took me on a road trip to see where the Bidor parangs are made. Upon arriving at the shop, I was surprised and impressed with how modern this place was compared to the forges I visited in the Philippines and Thailand. They also burned coal, but have recently upgraded to gas forges. Their facility uses power hammers, which makes things run a lot smoother and faster.

There is more of an assembly line atmosphere with about six workstations, complete with a forge for heating the steel, an anvil, a quenching tub, and an automatic hammer. This forge also makes knives, axes, and many agricultural tools supplying a large area of Malaysia. Their specialty is making parangs. I didn’t know of any other place in Malaysia that exports real authentic Malaysian parangs to the rest of the world, other than Outdoor Dynamics.

The Bidor brand of parangs features a plastic handle either in red or purple. They are also stick tang in design, but with an added feature of a simple metal pin that goes through the handle and blade, thus further securing it and preventing those accidental mishaps of the blade flying out of the handle. They make a variety of traditional styles of the parang: Chandong, Kota Belud, Bentong, and the Ray Mears-styled parang.

Every model has a slight difference, so the blacksmith must have years of experience hammering out the fine detail and capturing all the nuances that make each one different.

In August 2021, Knives Illustrated ran an article on bushcrafting with Malaysian parangs. It showcased how to use parangs in the way they were meant to be used—on bamboo, on wood, and for food preparation. All the parangs and goloks were blades supplied by the Bidor blacksmith while the handles, fit, and finish, were from MyParang.com based in Penang, Malaysia. Ahmad Nadir switched his focus to making the Bidor parangs even better than before—semi-custom parangs.

Honoring tradition, he offers four varieties of the Duku Chandong, with 8-inch and 10-inch blades, and two with 12-inch blades. One of the 12-inch blades is an extra weighted Duku Chandong for a heavier chopper with the same style.

The Lading pattern is offered in the My Parang lineup with a 12-inch blade and a slightly more squared tip. It has about 7 inches of sharpened blade area, giving a lot of real estate for choking up and other grips. The Parang Lading is also used as a weapon in the Silat Cekak (traditional Malaysian martial arts), other than as an agricultural tool. There are some slight differences between the everyday tool and the ones used in Silat Cekak. Traditionally, Lading-style Parangs were made to fit the user’s arm for fighting and training Silat Cekak.

The Tangkin parang has a very ergonomic dynamic. It works especially well when you are positioned low on the ground. The curve seems like it’s drastically sweeping upward. However, in a low position, it enables the entire blade to be used, especially the sweet spot, keeping your knuckles safe and out of the way.

If you have ever questioned the toughness of a stick tang chopper, you are not alone. Many westerners want a full tang or nothing. As far as I know, not one production knife company has ever offered a stick tang style parang, golok, E-Nep, or bolo. Rather, they are all full tang and usually too thin and are called bolo machetes, parang machetes, E-Nep, or kukri machetes.

Condor Tool and Knife offers many great, authentic-looking, and rustic patterns, mimicking the real deal only to be on the very heavy side because of the extra weight of the full-tang. This makes them parang, bolo, and E-Nep-shaped tools, yet a far cry from the authentic feel of the way they were meant to be. They’re light and whippy with a weight-forward feel, thick near the hilt and always thinning towards the tip (distal taper).

Some custom knifemakers have offered more authentic versions by forging the blades, and a few brave makers have done some stick-tang models with a pin. That being said, Westerners can’t fathom a stick-tang knife chopping, splitting wood via baton, or digging with a wood or plastic handle. On top of that, these tools are often kept outside, like most tools. However, it has worked for their culture for centuries, and I think they know best.

As my trip to these amazing countries ended, it was the start of a lifelong passion devoted to these long blades and the variety of patterns. The more a person sees, the more they come to find they’ve only scratched the surface. My quest for authentically made long blades is far from over. As for the places I’ve been to, I know one thing for certain—I must return!

My Parang

www.MyParang.com

What makes My Parang blades so reliable and nearly bombproof? The simple answer is that the company has been doing it this way for as long as steel has been around and it had access to it. The handle is made of wood and drilled out to allow the V-shaped tang to fit. Epoxy is added, and the blade tang is pushed in.

This is how it’s done in Malaysia and Indonesia. For the most part, it will be all that is needed. However, My Parang adds a pin hidden under the copper ring/bolster, which is also epoxied. This results in a solid one-piece tool that isn’t going anywhere, yet preserves the feel, weight, and essence these authentic tools offer that mainstream production companies have yet to produce.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article appeared in TREAD Jan/Feb 2024.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link