Jason Fogelson

.

October 25, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Jason Fogelson

.

October 25, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Everybody loves to go fast. But the faster you go, the more important your brakes become. For every ounce of effort that you expend on adding horsepower and torque to your sled, you should reserve some time, energy and money to optimize your braking system.

Like just about every other system on a car, proper brakes are all about balance. You need the right amount of braking power to match your vehicle’s weight and power, and you need the right kind of braking power to match your driving.

For instance, if you were setting up the braking system for a dragster, you would need to worry about maximum braking power without lockup, and you might even supplement your brakes with a parachute. You wouldn’t worry so much about brake-fade or brake-pad longevity—you’d set up for that one extreme stop.

“It is possible to put together your own brake system piece-by-piece. You can source rotors, pads, calipers, brake lines and master cylinders from your favorite vendors, and you can probably get the whole thing working. However…”

In contrast, if you were setting up your car for a long-distance drive like the Cannonball Rally, you’d want to find a braking system with long-lasting pads, fade-free operation and precision application. Your car is going to experience a wide range of driving situations, and your brakes may need to slow you down quickly and repeatedly without failing. The biggest, most powerful brakes might be woefully inappropriate for your Cannonball Run.

Whichever kind of car you’re building or whatever kind of driving you do, you need reliable, predictable braking to get the most out of your ride.

“What happens in this industry is that the brake system is a system. It is made up of a bunch of components that have to work totally together to give you the best results,” according to Warren Gilliland, president and chief engineer at TBM Brakes.

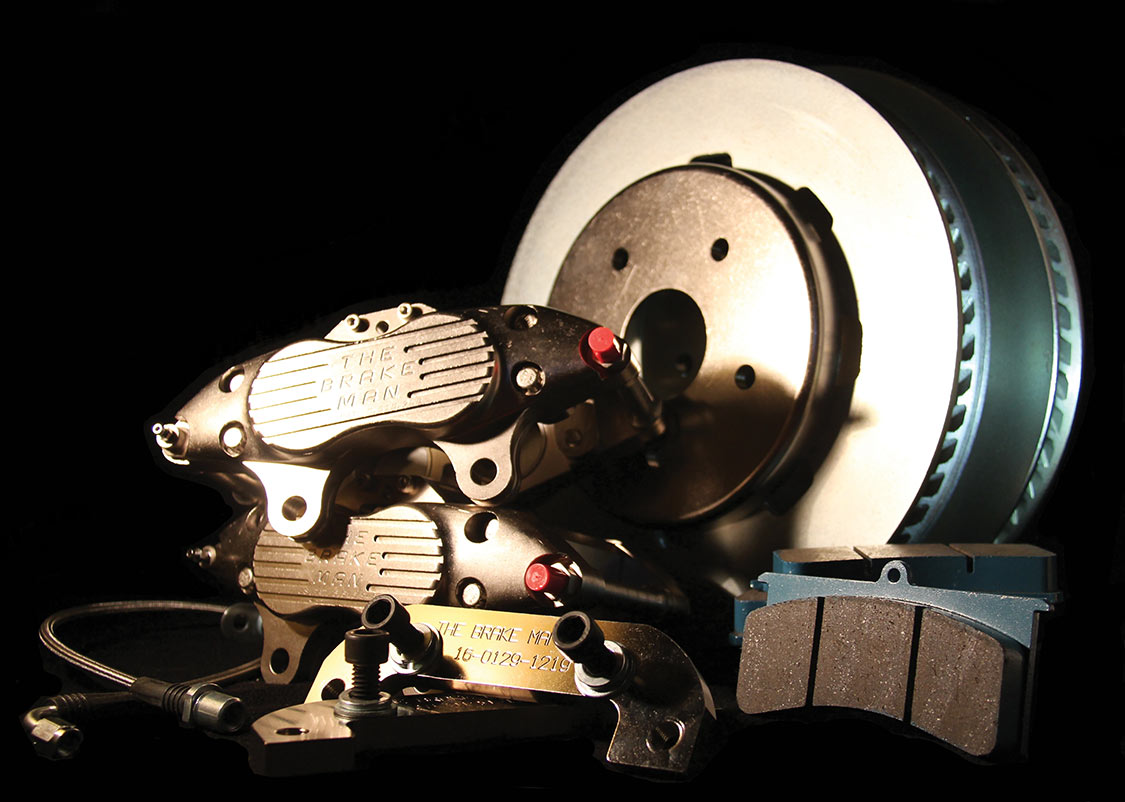

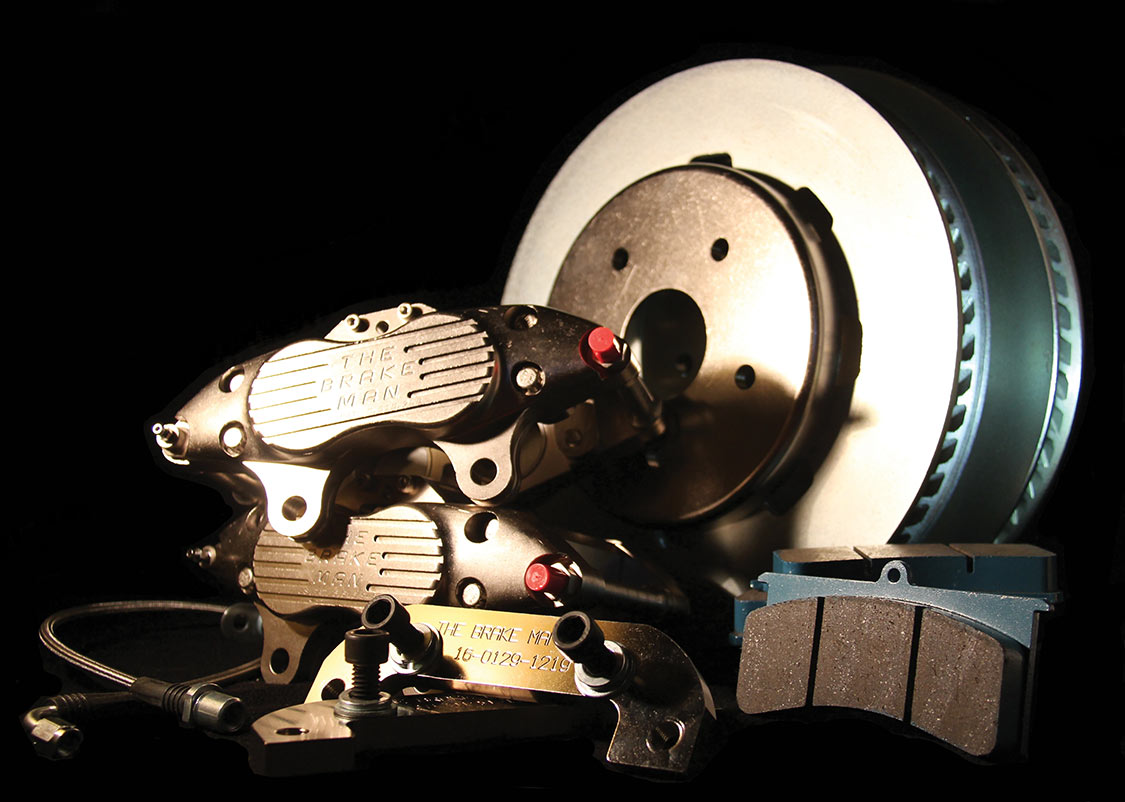

It is possible to put together your own brake system piece by piece. You can source rotors, pads, calipers, brake lines and master cylinders from your favorite vendors, and you can probably get the whole thing working. However, unless you’re a brake engineer, you’re missing out on the benefits of an integrated system from a single manufacturer. Not only are the parts designed to fit and work together, they’re also engineered to perform as a system, giving you the benefit of specialty brake engineering along with your purchase. “We supply a listing of all the components that are included in the kit in the installation instructions, should you ever need to order any part for any reason,” says Robert Roese of Wilwood Engineering. Each kit includes “detailed installation instructions, wheel clearance diagrams, calipers, caliper mounting brackets and hardware, rotors, aluminum hats, aluminum hubs (bearing cones installed) wheel bearings, grease seals wheel studs, brake pads and all necessary hardware to install the kit.”

Some of the leading manufacturers of brake systems include Brembo (Brembo. com), Wilwood (Wilwood.com) and TBM Brakes (formerly The Brake Man, Tbmbrakes.com). Disc brake kits start at about $400 per axle and go up from there, depending on features.

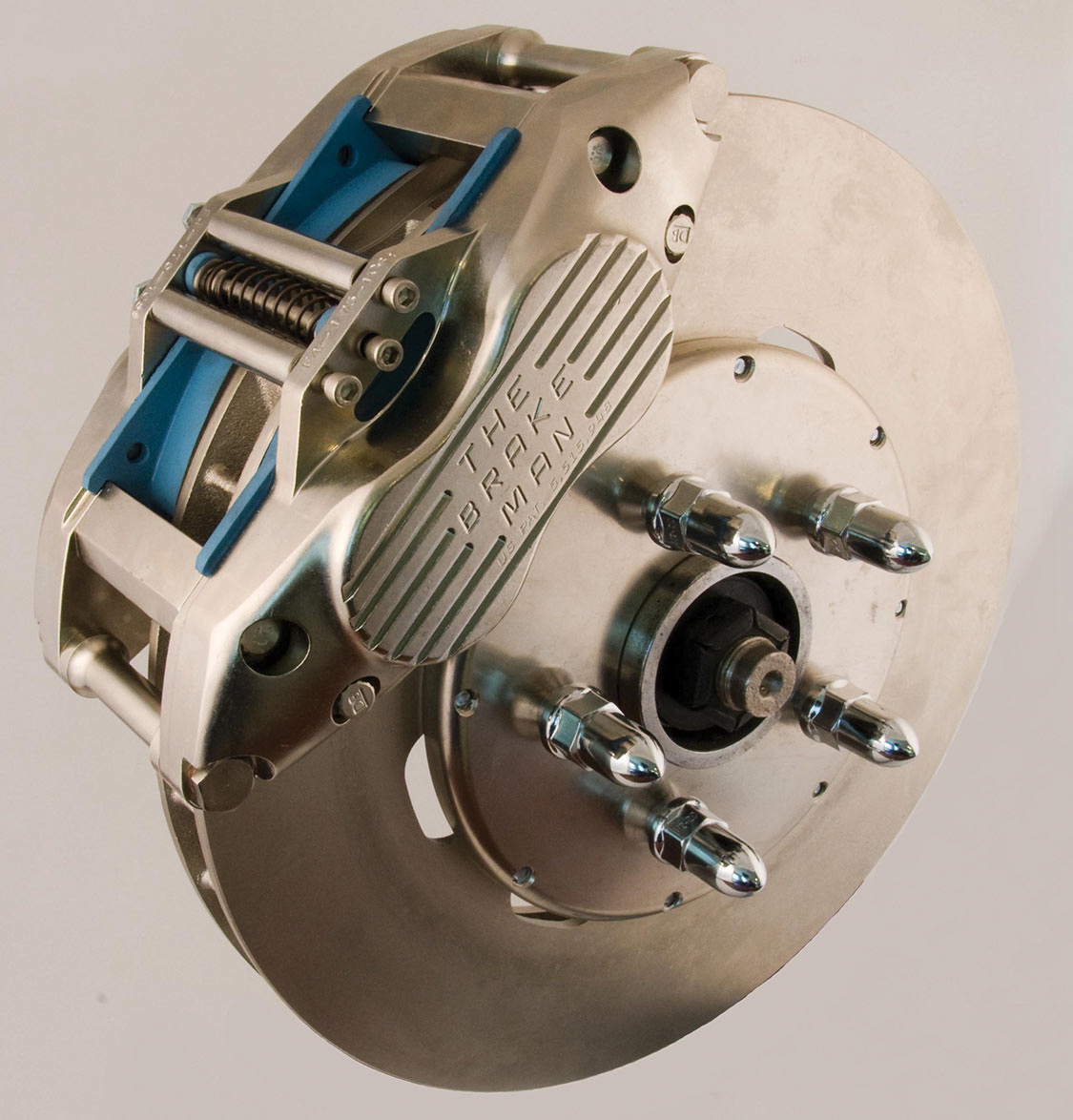

“The key to the braking system is the caliper. The caliper determines everything else that you must do to the brake system,” says TBM’s Gilliland.

There are two basic kinds of calipers you can mount over your disc to stop your wheels: floating and fixed. Both kinds of calipers do the same thing in the end. They each hold the pads ready to press against the disc and slow its rotation with friction.

Floating calipers are the most commonly installed versions on production cars. They “float” on a pin that is attached to the spindle and have pistons on only one side (the inboard side). The design has greater tolerances built in than fixed calipers, which (as the name implies) are solidly fixed to the spindle. Fixed calipers have pistons that move in from both sides of the disc, clamping the pads to the disc. There are more moving parts in fixed calipers, and more complexity, but the design is more efficient and effective, offering more feedback and ability to modulate the brakes with your foot. That’s why fixed calipers are more popular for racing applications.

Gilliland argues for the importance of rigidity in calipers. “The caliper provides the force to make everything else work in the system. The caliper you choose—if it is a very rigid or a very strong caliper—is going to require a lot less volume to make it actuate and make it release. By doing that, it allows you a much wider range of choices in which master cylinder you are going to use. The bigger the master you put on the car, the worse the pedal effort is going to be.”

Like almost everything else automotive, there’s a cosmetic aspect to calipers, too. With some wheel designs, calipers can be exposed to view. A beefy caliper painted, powder-coated or anodized in bright red or orange is a great look on a muscle car or hot rod, hinting at great braking power.

In purely simplistic terms, your front brakes provide the vast majority of the braking power in your car in most situations. It’s all in the physics: Applying the brakes shifts the weight of the car toward the front. That’s why front disc brakes are generally bigger than rear disc brakes on factory vehicles. Even today, some economy models roll out of thefactory with drum brakes on the rear wheels.

If you’re on a budget, or if you’re modifying your car in stages as time and money allow, start with the front brakes for the greatest impact. Installing disc brakes on the front wheels of early muscle cars that originally came with drum brakes “makes an impressive improvement in not only stopping distances, but reduces brake-fade and instills driver confidence,” according to Wilwood’s Roese.

If your car already has disc brakes, it’s a no-brainer. Stick with the discs and work from there. Disc brakes are generally more effi- cient than drum brakes, and it’s easier to get fade-free, predictable stopping from disc brake systems.

“Drums will expand under heavy braking effort,” according to Carl Pritts, tech advisor at Summit Racing Equipment. “Literally, the heat generated causes the drums to grow in diameter; this is commonly called brake-fade. When switching to discs, not only are you increasing the surface area the pad/shoe has to press on, but the disc will not be deformed by the high-pressure squeezing against it.”

Concours-level restorations and period-correct show cars will stick with the drums for authenticity, but if you’re seeking the balance of braking to performance, you may want to consider a disc brake conversion. As stated earlier, start with the front brakes.

If your rear drum brakes are in good shape, and you’re not going to be taking your car to the track, you can place a rear disc conver- sion low on the priority list, according to TBM’s Gilliland. “There is no advantage to change from drums to discs on the rear. Drum brakes are more than adequate for the street-driven car to give you a proper balanced vehicle, even under the most strenuous use on the streets.”

Disc rotors tend to fall into one of three categories: sol- id, drilled or slotted. There’s always the outlier that com- bines the drilled and slotted approaches, too.

Drilled discs or rotors work on the theory that holes drilled through the rotor in a pattern will help to dissipate some of the heat that’s generated by the friction of braking. The holes also serve as an escape for gasses that might build up during braking from the breakdown of pad material, and as a drain for water in wet conditions. The downside of drilling the rotor is that the holes weaken the disc, which can lead to cracking and brake failure over time.

Slotted discs show up in performance situations where the extremes of fade-free braking are required. As the name hints, slots are machined into the discs in patterns that help shed moisture and gasses. These slots don’t go all the way through the disc like the holes in drilled discs, so they don’t compromise disc strength as much. Nothing’s free when it comes to performance, although slotted discs tend to wear out brake pads much more rapidly than drilled discs do.

Drilling holes in a rotor, according to Gilliland, allows the heat to leak out across the face of the rotor, rather than flowing to the cool center.

There’s much more to the solid/drilled/slotted disc choice than meets the eye. TMB’s Gilliland cautions against quick assumptions about drilling or slotting discs. “The problem is that if you do it on rotors today you are defeating the ability of the rotor to properly cool. Everybody thinks that it is making it cooler and it is not,” he says. “The way that a rotor gets rid of heat is through radiant dissipation across the faces and also by having air that comes up through the cooling veins in the center. Those cooling veins in the center act like a fan. It helps to heat soak the surface heat that is being created between the pad and the rotor to the cooler center because cast iron loves to equalize itself on temperature.” Drilling holes in a rotor, according to Gilliland, allows the heat to leak out across the face of the rotor, rather than flowing to the cool center. “Plus you have removed the volume of that rotor. Now that lower volume is going to get heated to a higher temperature because all of the metal you took out with the holes isn’t there to properly handle the heat load.”

Wilwood’s Roese admits that choosing between disc types can be aesthetic. “One of the biggest reasons so many people prefer the drilled and slotted rotors is because of how it looks,” he says. “Having some large open wheels with a brightly colored caliper combined with some 13” or 14“ rotors just looks cool—sort of like artwork for your wheels.”

“One of the biggest reasons so many people prefer the drilled and slotted rotors is because of how it looks.”

One of the most effective ways to change the feel of your brakes from mushy to firm is to upgrade your brake lines. It’s amazing how much impact a new length of stainless-steel braided line can have on how predictable and firm the brak-ing operation feels under your foot. In the vast majority of modern cars, brakes are a hydraulic system, using the movement of fluid to create the movement of pistons. For part of the journey, the hydraulic fluid passes through hoses and tubes. From the factory, those hoses are rubber or some syn- thetic material that can resist deterioration from the fluid. With repeated application of the brakes, the rubber and synthetic hoses expand and contract as the pressure in them changes. Eventually, those hoses weaken and lose some of their ability to resist expanding with pressure, and that little bit of weakness comes across as mushy brakes. It almost feels like there’s a sponge under your brake pedal.

As with any system on your car, your brakes should be balanced and tuned to everything else that’s been done and the general performance level you are aiming to achieve.

“Stainless braided lines offer two improvements,” according to Summit’s Pritts.

“First they are stainless braided. The stainless will not expand. Second, the inner liner is PTFE or Teflon-lined. This type of liner also will not expand. What you get is a very firm brake pedal under all braking conditions.”

Stainless-steel braided lines can also be ordered with special color sheathes to match or contrast with your paint color, adding a cool look to your braking system.

Ultimately, given the importance of braking systems on any vehicle, so it’s critical to get them right. There’s little sense in overdoing it—there is such a thing as too much braking. Balance is the key. Don’t be afraid to ask questions when you get hold of an expert. Specialty brake companies are passionate about what they do, and they love to share their engineering knowledge and expertise with muscle car owners. So as you build out your car, you can go fast, turn hard and don’t forget to brake.

Share Link