James Maxwell

.

January 21, 2023

.

All Feature Vehicles

James Maxwell

.

January 21, 2023

.

All Feature Vehicles

The 1969 Mercury Cyclone series was an intermediate-sized car and came in only one body style, a fastback, which the factory named “SportsRoof.” The aggressive profile gave the machine an instant performance theme that not only looked cool, but the slippery shape also provided fantastic aerodynamics on high-speed NASCAR racetracks. During this era “Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday” really did apply, especially in the southern states where stock car racing was most popular.

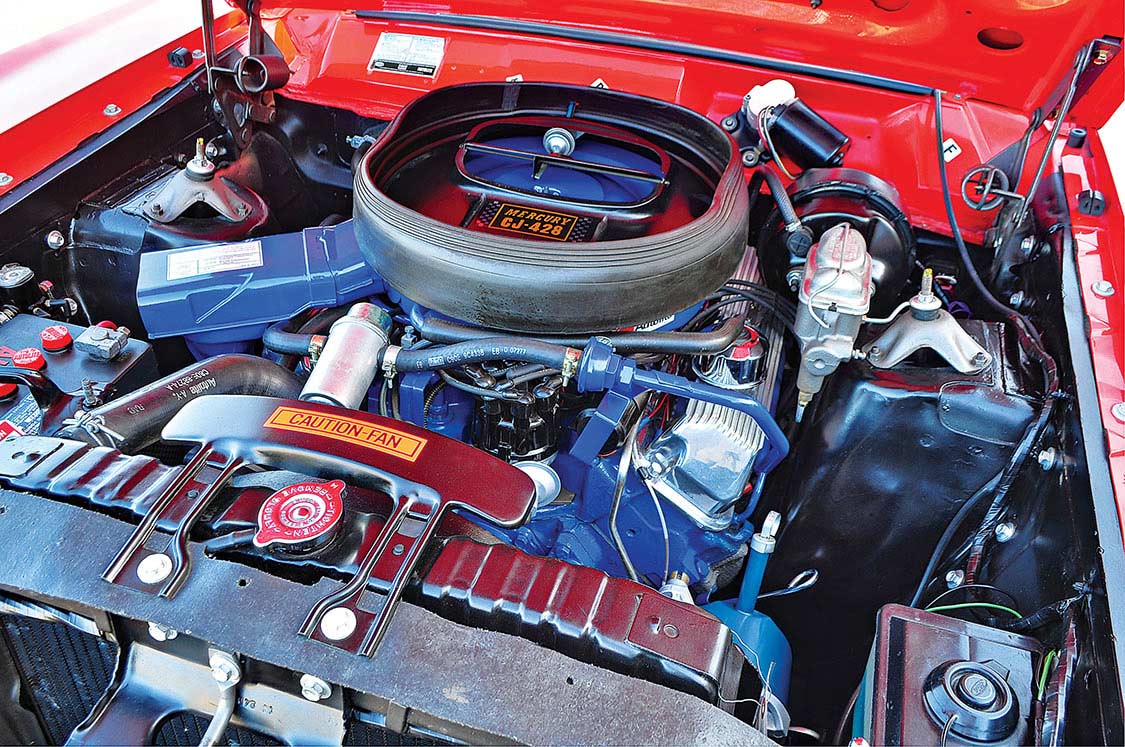

The top-of-the-line Cyclone CJ model came with a variety of upgrades, including a close-ratio Toploader 4-speed transmission, special sport suspension, 3.50:1 rear gears (9-in. ring gear diameter), dual exhausts, hood tape stripe and most of all, the Cobra Jet 428 engine.

This powerplant was the top-level version of the “FE” Series for 1969, incorporating a 4.132-in. bore with 3.984- in. stroke. The actual displacement turned out to be 426.544 cu.-in., however, Ford had decided in 1966 (when the Thunderbird and Police In- terceptor versions debuted) to label the engine as the “428” to not confuse it with the 427 engines.

By the end of 1968, the 427s were gone, leaving the 428 Cobra Jet as top dog in the FE family. (Originally FE stood for “Ford Edsel” as this engine family started in 1959.) One of the strengths of the block design is that the skirts of the cylinder block extend down past the centerline of the crankshaft by 2 5/8 in., providing a very sturdy bottom end.

The CJ 428 engine came equipped with 10.6:1 compression pistons (dished with built in valve reliefs), and used sturdy Police Intercep- tor connecting rods with large 13/32-in. nuts and bolts. The camshaft was a 390 GT item (hydraulic .481I/490 E lift, 270 I/290E-degree duration) using 1.76 ratio shaft-mount- ed rocker arms.

A 735-cfm Holley carburetor sat on a dual-plane Police Interceptor type intake, and large cast-iron four-into-one exhaust manifolds were part of the package. Horsepower was listed at 335, an innocent number that Ford selected to help keep insurance costs down for buyers as well as an aid for NHRA racers. According to retired Ford engineer Bill Barr, who headed up development on the 428 CJ, the actual maximum horse- power figure was 411.

In its January 1969 issue, Car and Driver magazine cranked out an impressive 13.94-second run down the 1/4-mile with a CJ428 1969 Cyclone, running 100.89 mph, using 3.91 fi- nal drive gearing.

Motor Trend in its August 1969 issue took a similar car down the track with 4.11 gears and ran even quicker and faster (13.85 ET at 101.69 mph), both of these tests showed the brute power of the Cobra Jet 428, especially with the fact that the vehicle that tipped the scales at 3836 lb.

When Cars Magazine got ahold of a Cyclone CJ to test in its June 1969 issue, this is how they summarized it: “The CJ is a strong-running, good-breathing, well-cammed super-wedge engine that has Super/Stock record-breaking potential. Yet, it’s super docile around town, reasonably eco- nomical and idles right down there with consumer stockers.

No stalling via loading up at low speeds and no bucking because of rough idle or wild cam timing.” With an au- tomatic transmission test car, they managed a best of 14.05 sec. elapsed time at 101 mph.

It should be noted that Joe Oldham, the editor at Cars Magazine in that era, later wrote a tell-all book “Muscle Car Confidential, Confessions of a Muscle Car Test Driver.” He explained that if the photos in the reports they published did not include a drag strip and christmas tree in the background, they simply guessed the car’s actual performance.

However, he had such a great feel for the muscle cars of that time frame that his seat-of-the-pants estimates were very accurate.

In December 1968, this particular car was delivered to a Lincoln-Mercury dealer located in North Caroli- na. The buyer had ordered it in early October and it came from the Lorain, Ohio, Ford Motor Company Assem- bly Plant, delivered with Competition Orange paint, and featuring the highly desirable “R-code” 428 CJ engine (with Ram Air induction).

A Select-Shift heavy-duty C6 automat- ic transmission was chosen along with power front disc brakes, power steer- ing plus selected options that raised the base price ($3207) to a selling price of $3955.20. Factory records indicate that 1693 CJ428 models were ordered with the R-Code powerplant.

Due to the location of the selling dealership (North Carolina is in the heart of NASCAR country), there’s a good possibility that the Cyclone was sold in a true and authentic Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday situation. During the 1968 racing season, racers like Cale Yarborough, Lee Roy Yar- brough (no relation) were tearing up the tracks and winning in their fast- back Mercury Cyclones.

The Cyclones in 1968 were the fastest thing on the track, thanks to the aerodynamic fast- back body style plus the front-end de- sign. The sloping center section of the hood aided in the cutting through the wind, especially on the longer tracks. Winning on the racetrack delivered a lot of positive publicity for the Mercury line, which translated to improved sales in the showrooms.

The pictured 1969 Mercury Cyclone Spoiler II is owned by Marty Burke of Leonard, Texas, and is a special car that came about as an answer to the Dodge Charger 500, which was aerodynamically improved over a standard 1968 Dodge Charger production car. The battles on the superspeedways with the “aero wars” were serious business during this era and Chrysler and FoMoCo were both hard at it in the wind tunnels for aerodynamic superiority.

Ralph Moody (of Holman and Moody NASCAR fame) was the guy respon- sible for the design and prototype work on the Mercury aero car (along with the Ford Talladega version that actually came out first) and he did it all in the company’s race shop located in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The elongated nose of this NASCAR-themed Mercury was fitted with a flush grille (sourced from a Ford Fairlane) that hung out some 6 in. longer than a standard front end. The nose was drooped at a 35-degree angle to the head- er panel between the hood and grille opening to better slice through the air.

The front bumper was actually a heavily reworked rear bumper off the same car, however, it was cut and veed in the center to fit the application. (The new front bumper didn’t have cutouts for turn signals so Ford truck blinker lights were installed behind the grille.) Mercury aero cars were considered superior to the Talladega because the nose angle of the Ford version was positioned at 30 degrees.

Besides the new longer and slippery beak, the rocker panels on these cars were re-rolled and moved upward by 1 in., which allowed the NASCAR race versions to be lowered by the same amount because of that being the measuring point during pre-race inspections.

It is believed just 503 total Cyclone Spoiler II cars were built, with 218 of them done in Presidential Blue and Wimbledon White (Dan Gurney Specials) and 285 came with Cale Yarborough Special markings (done in Candy Apple Red and Wimbledon). NASCAR required at least 500 cars be built to be considered a homologated production vehicle.

All Cyclone Spoiler II cars were factory fitted with 351-4V V-8 engines built at the Windsor, Ontario, Canada, plant, with column-shift automatic transmissions. The fitting of a rear deck airfoil-type wing on Cyclone Spoiler and Spoiler II cars is where the “Spoiler” name was derived.

As a result of these wind-cheating FoMoCo cars, Chrysler Corporation was forced to up the ante in the aerodynamic one-upmanship game by releasing the high-winged, pointed-nose Dodge Daytona Charger for 1969, followed by the matching Plymouth Superbird for 1970. By 1971, the NASCAR rules had changed and these special cars with their big-block powerplants were “outlawed” for competition. Cars were allowed to race only with an engine of 5-liters (305 cu.-in.). The big-block era in NASCAR was over. — James Maxwell

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared in the March 2017 print issue of the Drive Magazine.

Share Link