Lou Leto

.

June 25, 2021

.

All Feature Vehicles

Lou Leto

.

June 25, 2021

.

All Feature Vehicles

Corvette: if ever there was an American car that immediately conjures up recognition, memories, fantasy, inspiration and aspirations that would be it. By 1966, Corvette had been the halo of the American performance car for 13 years. Despite a slightly rocky start, once the market took hold of that fantastic plastic play toy that debuted in 1953, Zora Arkus Duntov and his engineering team, with the blessing of the designers first led by Harley Earl then later by Bill Mitchell, molded and matured the ’Vette to become a serious piece of magnificent hardware. The two-seater earned a global reputation on the street and the track. By every account Corvettes were purely American with big, wide bodies, gleaming chrome, engines that belted out lots of horsepower and tremendous torque with an exhaust exiting in a seductive, signature note.

By 1966, the fabulous styling introduced just three model years prior had become fully realized.

You could say that the 13th year of the Corvette was indeed a lucky one. The evolution was akin to a three-two-one countdown, as nearly each model year offered continuous and highly noticeable improvements from the model year that came before it. The 1963 Corvette took the world by storm by offering a sensuous new fastback-styled coupe body, hideaway headlights, and for the first time, independent rear suspension. Two years later, 1965, brought disc brakes to all four wheels, eliminating the four-wheel drums found on the first 12 model years. For 1966, Chevrolet offered the Corvette with serious new engine options. Among these was the ultimate level, 427-ci (7L) lump referred to as a “big-block.”

In America, it seems bigger is always better, and this big-block was no exception. It had an awe-inspiring horsepower rating when the L72 option was ordered. Rated at 450 hp during early 1966 production, the insurance naysayers put so much pressure on the manufacturers that midway through the model year, Chevrolet trimmed the output ratings to 425—on paper—without bothering to change any of the engine internals (11.0:1 compression, solid lifter camshaft, four-bolt main bearing caps). Keep in mind that OEMs were not exactly kowtowing to all of the insurance companies’ edicts, since even the original 450-hp rating was understated.

The buying public heartily responded to the new engines, ordering 19% of the total 1966 Corvette production with the L72 option. An interesting bit of trivia: purists still perceive true sports cars to be open roadster-style cars, since slightly less than ten thousand coupes were sold, while the drop-top body style sold nearly double that number.

The L72 Corvette is a pinnacle car that is on the radar screen for any and all serious enthusiasts. This is the exact reason this Silver Pearl Corvette is deeply entrenched in the Wehage family. It’s a personal, proud and sentimental connection that was owned and cared for by the late family’s patriarch Ken.

This Sting Ray is a numbers-matching rarity, never tampered with or modified in all of these years by any of the three owners in its history. It is a stellar example of a Corvette that is well preserved: the exterior paint and interior are assumed to be original. With 93,000 miles on the odometer, it has been driven spiritedly, but not abused. Originally sold by a Chevrolet dealer in Orange County, it remains within that county today.

Corvette fanatics and aficionados who lust for the minutiae would delight in learning the option list and narrowing down the exact number of models produced in 1966 with some of the equipment. Here are a few examples to track: 1966 Corvette coupes, 9,958 produced; 427 L72-powered ’Vettes, 5,258 convertibles and coupes built; Silver Pearl Corvettes, 2,967 painted this color; cast aluminum wheels, 1,194 produced with this option. Those who want to do the calculations to cull it down to even more exclusivity for this particular Corvette should also consider the other rare option combinations: teak steering wheel, transistor ignition and the option even rarer than dual side pipes, the factory off-road exhaust system. Then there is the unusual factory radio-delete plate, all the better to prevent any distraction from hearing the engine, one would assume.

Walking around this vehicle provided a discovery with each glance. Once the viewer gets past the aura that makes the C2, the nuances become noticeable. There are so many design nuances, some blatant, many others subtle, that catch the eye and capture the light; angular and curved lines, blended together to cheat the wind and delight the emotions. The color may be Silver Pearl, but it flows over this beautiful body like liquid mercury, quicksilver.

Since “Drive” is an element of our magazine title, driving becomes an important and emphasized component. Preparing to enter the cockpit, one immediately notices that the top of the door panel curves and intrudes into the roofline, much like a limousine door.

The true purpose of this allowance is not for an entrant with a large bouffant hairdo, it’s to allow easier ingress and egress while wearing a helmet, reminding that it was designed to make it easier for racing team driver changes during 12- or 24-hour competitive events. Holding the door wide, one can see the multitude of chromed handles and cranks on the interior door panel. The vent window has its own crank control, as does the main side window. The door pull is a chrome accent, tilted to give the illusion of motion.

Sliding into the bucket seats, sporty yet stylish in appearance for the era, takes the driver or passenger back in time. They are low-backed and flat, without form-fitting side bolsters. The teak steering wheel is elegant, thin rimmed and large in diameter. Looking through, the two large gauges tell the driver the important measurements of engine revolutions and road speed. The ancillary gauges report engine temperature and oil pressure or indicate electrical charging status. All are easy to read at a glance.

The double humped dashboard with the waterfall-style center section separates the business of driving from the enjoyment of going along for the ride. That vertical blank space, where there is no radio, does not appear to be obnoxious or that something is missing. Just over the dash, one can look out and sight the road or track ahead, framed through the fender peaks that are elevated higher than the sculpted hood. The feeling of the cockpit is purposely intimate, not claustrophobically tight. The enjoyment of the drive is the obvious emphasis of the Corvette. The pilot and passenger are involved, unlike the wide expanse of the GM passenger cars of the same era where the occupants just floated down the road in luxurious living room-sized environments.

Turning the ignition key immediately sets many mechanical sounds in motion. The 427 engine fires up without protest. It is a big-block, so it is best to let it idle for a time to allow the temperature to reach optimum range. Depressing the clutch does not require too much effort, and the factory shifter, with a lockout reverse feature, is mechanical and firm. Underway and going through gear changes, the big-block engine gains revs smoothly and quickly without protest or hesitation, though the camshaft does like it better in the higher range. The aural experience is very mechanical, yet not so loud as to prevent a conversation between cockpit occupants. Suffice to sum up the street-drive experience as: this Corvette will pull hard when asked.

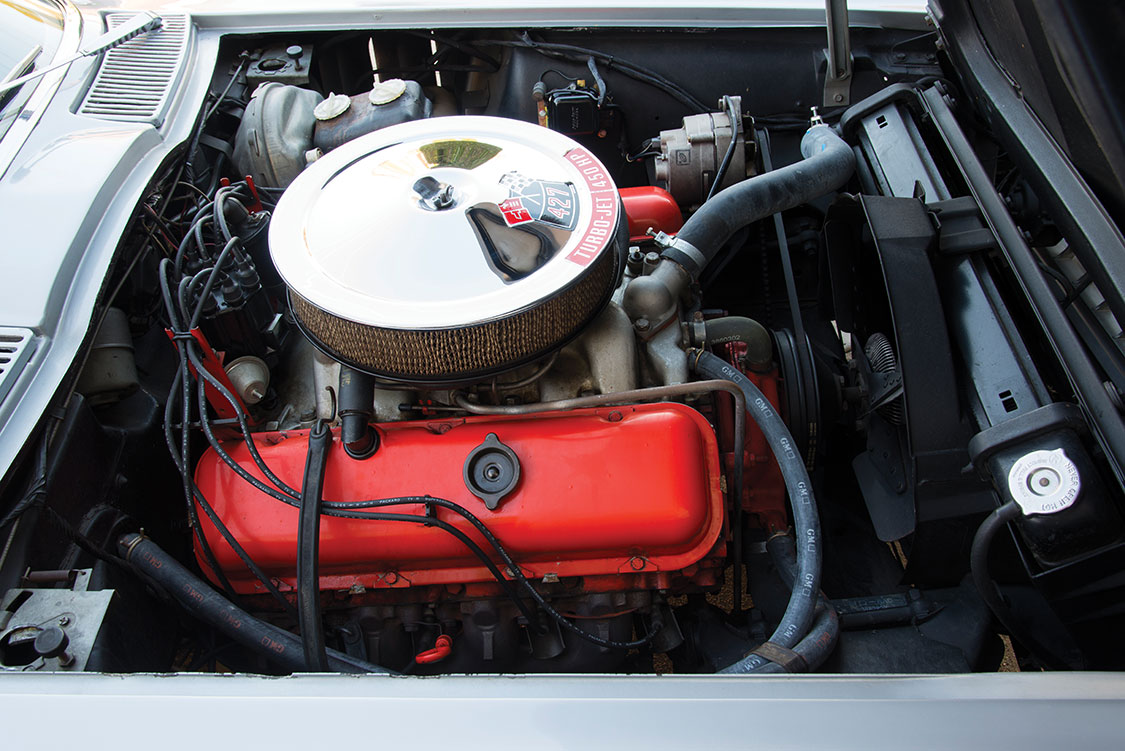

Resting under that sculpted hood, one notices that the 427 doesn’t need to call a lot of attention to itself. The primary chrome is on the top of the air cleaner. The sticker does mention the early year rating 450 hp of the turbo jet. The massive valve covers painted in signature Chevrolet Orange. Color signal that this was factory built for performance, not to show off.

This silver C2 beauty is a rarity, in options and in unmolested condition. All who have an opportunity to see or experience this Corvette should feel fortunate and grateful. Betty and the Wehage children for preserving both the memory and the vehicle as a tribute to its late owner/driver.

Text by Lou Leto

Photos by Guy Spangenberg

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link