MARCEL VENABLE

.

May 24, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

MARCEL VENABLE

.

May 24, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Recently I had a friend of mine fly into Los Angeles for a visit to Southern California to attend the Grand National Roadster show. Since the show takes place each year in January, it attracts many hot rodders and fans of the kustom car culture from numerous far off places where the weather is far less desirable.

Once we grabbed my buddy’s suitcase and navigated the horrendous traffic inside the terminal, we drove towards even heavier L.A. traffic to our final destination, close to the GNRS host hotel. While we drove, I thought it would be fitting to call out a few points of interest that pertained to the history and foundation of the hot rod industry. This was a fairly easy for me because I grew up in the area around west L.A., or to be even more specific for my fellow Angelinos, the South Bay.

My friend from the Northeast was fascinated by the buildings we passed where eccentric minds tooled machines to make them faster, or in some cases look unique. I went on to explain that it wasn’t a real estate broker’s dream that most of these guys were all located in close proximity or that they stuck together. No, it was really about the time more than the place. Let me paint the picture for you as well.

Before World War II, the migration to California was in full swing. Fertile land and warm sunshine were abundant, once John Mulholland brought water to the L.A. basin, turning a desert into paradise. People from all over the country flocked to Southern California searching for a better way of life away from areas like the dust bowl of Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska, or away from the oil fields of Texas and Louisiana where the heat could turn a young man into an old one in a hurry. The “Garden of Eden” weather mixed with wide-open land opportunities was intoxicating to everyone, rich and poor.

The wide-open spaces of Southern California made an automobile a requirement. Before the war many automotive mechanics serviced cars during the day but yearned for speed at night. These thrill seekers dove into the power plants of anything with four wheels searching for more power to propel them down the streets and highways of their newfound paradise. When their vehicles seemed to be too much for the country roads turned urban city streets, the group moved just north of the L.A. city limits to the dry lake beds of El Mirage where sometimes five or six cars tried to out run each other all at the same time, sometimes even in different directions! Whoever had the fastest car was the man to be, almost regal, and others would strive to be like him, or were envious of him. Innovations, including modified intake manifolds, modifications to the camshaft and less restrictive exhaust systems, were born here during this time and speed was king!

After the war broke out, the country went to work to beat the axis forces. The thrill-seeking hot rodders went to work as well, even gaining an education from the machines that helped to win the war, as most of the fast garage mechanics from the Southern California area built or serviced tanks, planes and ships, while receiving three hots and a cot plus pay from Uncle Sam. Once the boys came home it was game on for speed, as the government thanked some of our boys with loans to start businesses to strengthen our military and our economy. Southern California was a hotbed for these types of skilled people and military defense companies sprouted up throughout the area.

Even though there wasn’t a war to fight, tanks, planes and Navy installments still needed producing, but this time for profit. The automobile benefited from the education these thrill seekers got during their military service. What they had learned in the military was now being put to use on the streets. With SoCal calling the shots, a small area of western L.A. referred to as Thunder Alley sprung up in Culver City, which had mainly been known as a big studio city by the beach. This was a perfect diversion because most visitors were star struck from the movies and never paid attention to the roaring sounds of engines screaming up and down Jefferson Boulevard.

Speed was the in thing for many years after the war, and hot rodders didn’t disappoint. They improved the internal combustion engine’s efficiency and overall power 10 times over, and proved it at the many notable areas throughout the greater L.A. area. The racing stadiums that helped sell easterners to move out west during the first half of the 20th century were still there. Arenas like Gilmore Stadium in the heart of the west side, along with Culver City Stadium, allowed the sultans of speed to run amok under the palm trees and searchlights with all of Hollywood watching.

So just as I had the pleasure of driving around the streets of Southern California like a tour guide, I’d like to share with you just a few of the standout places that I saw while I was growing up. Please join me in a trip down memory lane as we check out how things looked way back when compared with what they look like now. I invite you to share with us the places that influenced your area. Please log on to Facebook at Maximum Drive Magazine and share pictures and stories of old shops, strips or cruise spots that got you into this hobby!

4921 West Jefferson Blvd.

Located at 4921 West Jefferson Blvd. in Culver City, this is the post-war facility of the Edelbrock Corporation. Occupied from 1950-68, this is where Vic Sr. and Jr. fashioned speed equipment from the flathead Ford engines that started it all to the fancy new overhead valve engine that we all know today as the small-block Chevrolet. As you can tell from the photo, it’s easy to see that business was booming for the Edelbrock family, as the two Edelbrock men pose in front of one of the entrances to the east garage.

411 Coral Circle

By 1968 Edelbrock outgrew the Jefferson shop and was in need of a new location. The new building, located at 411 Coral Circle in El Segundo, was home to the Edelbrock Corporation for the next 19 years. It was in this building where iconic intake manifolds such as the Tarantula and the Torker units were designing and machined. The awesome photo below of a Super Bee towing a Duster gives you a great idea of what was going on around those times. Today the building is in a transitional state, and the only remaining clue that it once was headquarters to the Edelbrock empire is the orange tile with the slick-looking address numbers.

9599 W. Jefferson Blvd.

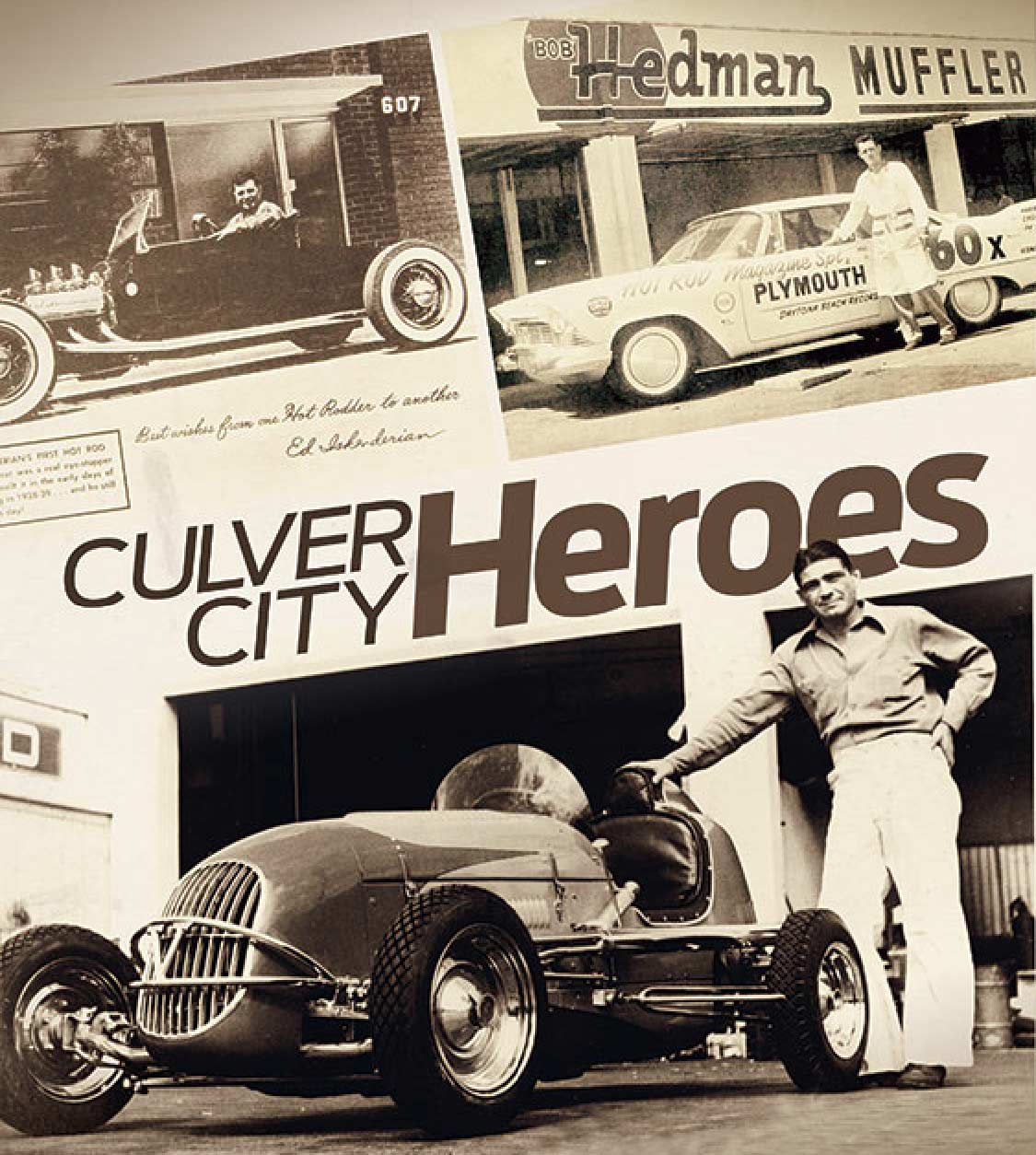

One of the major components from the early racing scene that greatly improved the horsepower and torque of these early hot rods was a tubular exhaust system called “headers.” Although there were many mom and pop muffler shops building these systems for local trill seekers, no one took on the tasks of manufacturing this type of exhaust system like Bob Hedman.

Once the boys came home it was game on for speed, as the government thanked some of our boys with loans to start businesses to strengthen our military and our economy. ”

His Hedman headers were one of the must-have parts for hot rods. He began as a one-man shop in 1954, where he originally built headers for fellow racers who competed alongside him for the extra cash to pay for his own racing hobby. By 1957, his hobby turned his one-man shop into a full production manufacturer of header manifolds as seen in some of these shots taken by Eric Rickman back in 1957.

By the late ’60s, Bob had outgrown the original muffler shop and his first manufacturing plant on Leahy St. in Culver City. In the early ’70s, Hedman Hedders moved to a new location at 9599 W. Jefferson Blvd. On the previous page you seen how the facility looked like back then, and above is how it looks today as an animal hospital located just down the street from a dog park.

Speed was the in thing for many years after the war, and hot rodders didn’t disappoint. ”

Bob was a racer’s racer and took more than just a casual interest in his hobby, becoming one of the founding members of SEMA, along with a few other Culver City manufacturers, including Vic Edelbrock Jr. and the Camfather himself, Ed Iskenderian.

Today, Hedman headers are still made here in the United States in two locations: Whitter, California, and Alpharetta, Georgia. The company still manufactures professional-quality header-style exhaust manifolds for just about everything on four wheels. Throughout the years, Hedman has branched out to a few specialty header systems such as the Hustler line, Trans-Dapt and Hamburger’s Performance Products all forming Hedman Performance Group.

6338 West Slauson Ave. 16020 S. Broadway

Ed Iskenderian was born just outside of Tulare, California, in 1921. Back then cold temperatures created several heavy frost nights that forced his family to move south to the L.A. area. In high school, Ed fostered his love of mechanics and built his first car, a Model T roadster. After graduating from high school he went to work as a tool and die maker, where he learned to be a machinist. When World War II broke out Ed joined the Army Air Corps, later named the U.S. Air Force, where he served with the Air Transport Command flying supplies to the Pacific.

Upon his arrival back to the States, Ed jumped right back into his T-roadster project. While rebuilding his V-8 engine, he ran into a snag trying to obtain a special camshaft for his engine. The overflow of work from the war effort proved overwhelming for the local machine shops who would grind camshafts for young hot rodders, so Ed, with help from some good friends, located a cam-grinding machine. Decades later, Ed came to be known on the dry lake beds, city streets and race courses around the world as the “Camfather.”

The first Culver City shop was located at 5977 Washington Blvd. before Ed bought an empty lot for his new building on 6338 West Slauson Ave., just around the corner from the famed Thunder Alley in Culver City. In 1950, Isky moved across town to Inglewood to a larger shop on Western and Pico Ave. Some time around 1968, Ed moved over to the current location at 16020 S. Broadway in Gardena. This massive four-building complex is more than 75,000 sq-ft and takes up almost a full city block. Ed has employed more than 100 specialists and engineers for more than 60 years, and he’s still very involved in day-to-day operations.

Ed can be seen almost every day at lunchtime at the local burger place just a few blocks from his shop with his good friend Nick Arias Jr. and John Athan, the man who helped Ed find his first machine to grind cams. The legend of Isky Cams lives on, as he’s recognized by many of the racing sanctioning bodies the world over. Reminders of racing vehicles both old and new line the showroom of his place like a shrine from the racers who have realized their goals through Ed’s genius. To this day, the Iskenderian Racing Cams sign is a predominant landmark in Culver City, serving as a reminder of the area’s racing roots.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link