Rod Short Rod

.

August 22, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Rod Short Rod

.

August 22, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

The turbulent ’60s was a decade of change. Civil rights, Vietnam, rock ‘n’ roll and the sexual revolution all reshaped American culture, and the golden age of the muscle car became a big part of that change as well. Everything came to a head 50 years ago in 1965, which is where we begin our story.

In the early ’60s, Stockers (as they were called then) were getting more and more popular as a spectator attraction. The fledgling NASCAR used that to establish itself in the minds of both the public and the auto manufacturers, but Detroit saw that grassroots drag racing was closer to the hearts of potential buyers.

NHRA also capitalized on this concept as the family sedan gained serious performance. New classes within Stock Eliminator opened up as well as relaxed rules that allowed open exhausts, aftermarket ignitions, new tire compounds and different gear ratios, which provided a boost for the performance aftermarket. One could easily buy the same car off the showroom floor that was being raced in NHRA’s top stock classes. In 1962, NHRA formed a Factory Experimental class for cars different than what came off the assembly line. Super Stock class was the top of the food chain for production cars equipped with only assembly line parts and equipment. FX cars were a far different breed.

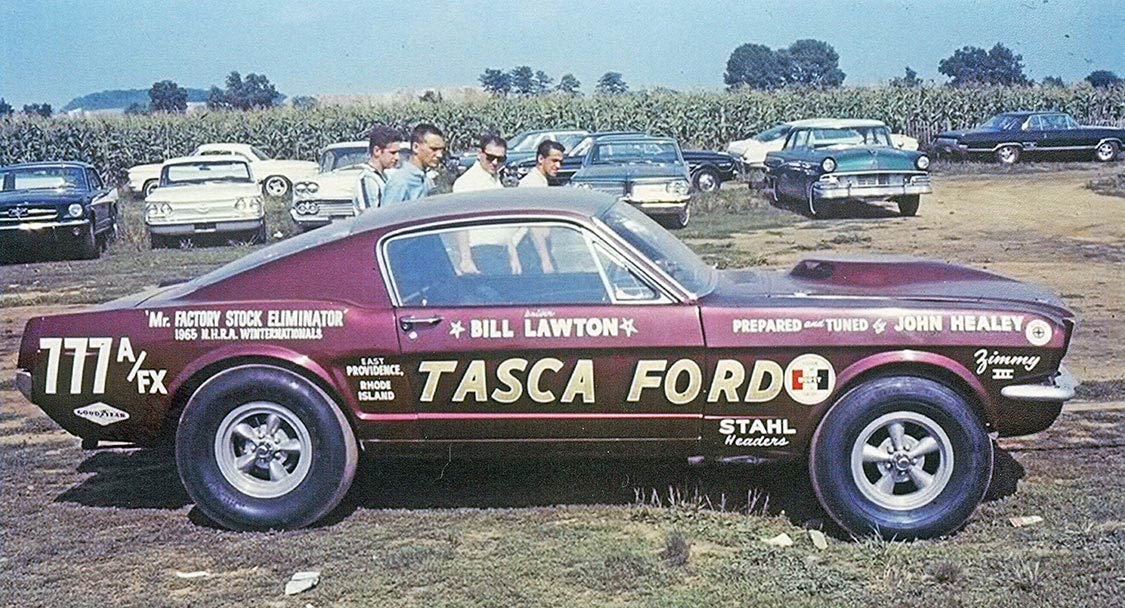

What really was a Factory Experimental? In 1965, the NHRA rulebook explained that FX classes were reserved for 1965 model year stock automobiles only using factory optional equipment which didn’t have to be necessarily factory assembly installed or showroom sales available. Cross breeding from one year to another was not permitted. Essentially, Factory Experimental (FX) was a showcase for Detroit to sell built performance cars with non-production modifications and parts.

By 1963, the handwriting was clearly on the wall. Stock and Factory Experimental had become the most popular spectator classes.

There were three class designations in FX, all of which were determined by the total car weight divided by the total cubic inches of engine displacement. They were A/FX (7.50 to 8.99 pounds per cubic inch), B/FX (9.00 to 12.99 pounds per cubic inch) and C/FX (13.00 or more pounds per cubic inch).

Of course, there was some fine print. Any engine or options listed by the automobile manufacturer for the engine model used were accepted, provided the engine and options were accepted by the NHRA. Superchargers were not accepted. Vehicle bodies were required to remain in their original production location, but the axles could be relocated a maximum of 2% of the total wheelbase from the original stock location. Wheel wells and fenders could be altered to permit installation and removal of wheels/tires, but could not extend outside of the fender and body lines.

The bottom line, however, was basically this: stock meant stock. The only performance options approved for this class had to be available on the assembly line, announced prior to a publicized date and approved by NHRA. Otherwise, the car would be put in FX.

By 1963, the handwriting was clearly on the wall. Stock and Factory Experimental had become the most popular spectator classes. Even so, General Motors dropped out of racing, partly because they were already the best-selling brand. Rules were once again loosened (albeit slightly), while safety items such as seat belts and helmets became mandatory in FX.

With Chevrolet officially out of the picture, Ford and Mopar struggled for dominance on the drag strip. Despite the success of the Dodge and Plymouth 426 Stage III wedge, Ford won the 1964 Super Stock championship with its 427 Ford Thunderbolt. Mopar saw the smaller T-Bolts had an aerodynamic advantage, which they knew would carryover in 1965 when the Mustang hit the tracks. They also saw the lighter Ford 427 as having not only a weight advantage, but also slightly more horsepower as well.

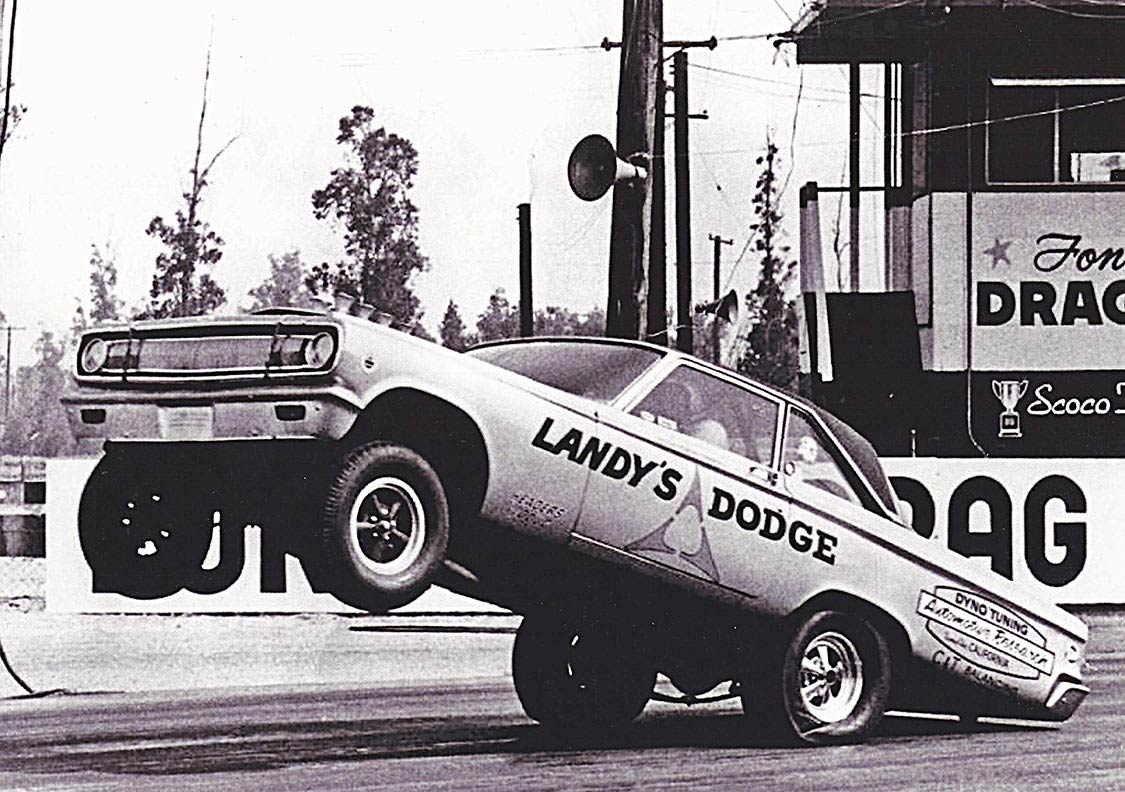

With that, Team Mopar developed altered wheelbase (AWB) Dodge and Plymouth entries, which immediately prompted an outcry from the Ford camp that they had gone too far. Insisting the AWB Mopars either taken out of competition by the factory or put back into original condition, Ford mounted a public relations campaign against them and won. NHRA said that the cars were built in full awareness of the maximum 2% wheelbase alteration rule and disallowed their participation in FX at the NHRA Winternationals. The AHRA, on the other hand, believing that handicap formula would equalize the competition, allowed the AWB Mopars in. Fearing embarrassment on the track, the factory Ford teams were forbidden to race against the AWB Mopars.

Beyond NHRA- and AHRA-sanctioned events was another story. Fast stock-bodied racers drew large crowds, were big money and received much media coverage, which helped rewrite the story of drag racing. Racers did everything to make their machines as fast as possible. In addition to altered wheelbases, stripped interiors, engine setbacks, lightweight components and acid-dipped bodies began to appear. FX cars soon abandoned carburetors in favor of fuel injectors and even superchargers as nitro and hydrazine found its way into the fuel tanks. Exhibition stockers began to run as quick or quicker than Gassers and Altereds.

As modifications got more outlandish, the gap between what was a stocker that anyone could buy and what was on the track became more extreme. As racers went to fiberglass bodies and then tube frames with flip-top bodies, the final link to what was once a production car was finally gone. Although it was agreed that the Ford and Mopar drag racing programs sold cars, these automakers began to devote less and less time and money to the development and sponsorship of drag racing programs.

By 1966, Factory Experimental was gone as a class in NHRA, but it sowed the seeds of both Funny Car and Pro Stock, and in later years Pro Modified as well. Fifty years on, its essence still lives today.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link