CHRIS COLLARD

.

July 25, 2023

.

Feature Stories

CHRIS COLLARD

.

July 25, 2023

.

Feature Stories

Before heading to Easter Jeep Safari this year, I did a final walkaround of my car hauler, an 18-foot Big Tex with my Expedicion de las Americas CJ-7 atop. As I inspected the tie downs, lights, electrical connections, tires, and safety chains, I thought of the dozens of towing accidents I’ve seen over the years and wondered what factors led up to having someone’s possessions strewn across the highway. In this Backcountry Skills, we’ll be exploring the equipment and discussing techniques of safely hauling our precious cargo, and how to avoid being the purveyor of the next Interstate yard sale.

I have five trailers ranging from a small box unit for dump runs to a 26-foot toy hauler and tandem-axle sailboat trailer. But my first experience with toys on the hook was at age 16—my dad let me take friends out on our ski boat…what was he thinking? I learned the principles of wide turns, double-checking the coupler and wiring, and how to back the darn thing up without looking like a rookie. But as my trailers got bigger and loads got heavier, I realized there was a world of stuff I didn’t know.

There are a variety of methods to tether a trailer to your rig ranging from the standard ball and socket, pintle, gooseneck, and fifth wheel. We’ll focus on the former, which falls into five classes. Class I & II are light duty, so we’ll skip those, but the following principles apply to all methods and classes of towing.

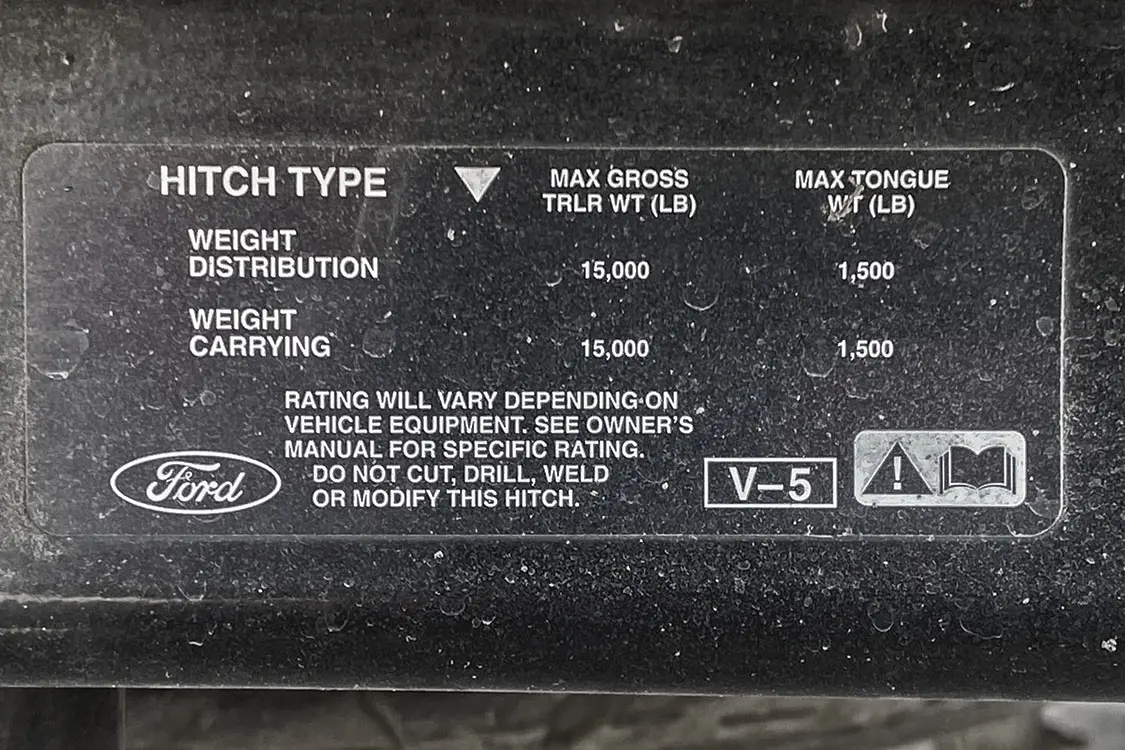

The Department of Transportation (DOT) specifies load testing guidelines for receivers, ball mounts and pintles, safety chains, and related components under SAE standards. For example, Section J684 applies to vehicles with a gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) of less than 10,000 pounds. It states the maximum advertised load (stamped on the hitch or receiver) is derated by two-thirds of its minimum tested breaking strength. Thus, a hitch rated at 10,000 pounds must have a minimum failure load of 15,000 pounds.

Interestingly, straps and tie downs for non-commercial use apparently fall under Wild West law…anything goes. I use gear from Mac’s Custom Tie Downs and reached out to company founder Colin McLemore for advice on this. He confirmed there isn’t a governing body regulating tie downs, and the most important thing is to utilize two separate attachment assemblies fore and aft, and buy the best system you can afford. He added, “Are you going to trust your $60,000 Jeep to $30 big box store straps?”

TIP: It is important to remember that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Make sure each component is rated for the task at hand.

If the following sounds like a pitch for Mac’s, it is. Why? Because most of their gear is made in the USA, straps are hand-sewn in Idaho with U.S.-manufactured webbing, and if a component doesn’t pass QC it is tossed in the trash. As a military supplier, Mac’s invests extensively in R&D, engineering, and functional ergonomics (i.e., their webbing’s rated working load limit is 33 percent of actual breaking strength). I personally dig their Monkey Face stake-bed anchor points and articulating snap hooks, which feature a thumb lever for single-hand operation. If you need a specific-sized tire net, they’ll make it to order. Enough said.

TIP: Each component in a tie-down system should have a tag indicating its working load limit and manufacturer’s name.

The most common wiring connectors are the flat four-pin and round seven-pin. The former manages basic lighting, while the latter has additional leads for reverse lights, electric trailer brakes, and auxiliary power (seven-pin to four-pin adapters are available to simplify choosing a seven-pin).

Depending on where you live, trailer brakes are required for loads as little as 1,500 pounds. Regardless of local statutes, they are a good idea. The reason is twofold. Your vehicle’s braking system was not engineered to stop an extra, say, 6,000 pounds. But more importantly, if the trailer is stopping its own weight, it won’t be trying to push your rig into the next county. I’ve witnessed some horrific towing accidents, and most were attributed to improper tongue weight or ineffective trailer brakes. You will also need a brake bias modulator, which allows the driver to increase or decrease trailer brake bias depending on conditions.

The most common mistake I see people make is miscalculating tongue weight. This crucial detail, or oversight thereof, is the root cause behind the majority of trailer-related mishaps. The reason is that too little tongue weight loads up the front axle and lightens the rear. Conversely, too much tongue weight increases rear axle load and makes the front end want to ‘float.’ Both conditions negatively affect how your vehicle steers and how it brakes, as well as the ability to control it during not only emergency situations but normal driving as well. Having said this, setting the appropriate tongue load is paramount.

An RV trailer is designed to have a tongue weight between 10 to 15 percent of its curb weight. It is important to keep within these parameters when you load it with equipment, fuel, UTVs, or motorcycles. I’ve used conventional hitches for decades, but usually for small utility trailers or boats. When I purchased a car hauler and started towing various vehicles, setting the right tongue weight was a bit of a mystery.

TIP: Tongue weight should be 10 to 15 percent of trailer weight and not exceed load limit of coupler components.

I found the solution at the SEMA Show in the form of Weigh-Safe. Their beautiful CNC-milled aluminum hitch, which is available for up to 21,000 loads, has a scale built into the draw bar. Just pull the vehicle onto the trailer until the scale hits the target tongue weight, and voilà! To expedite loading, I’ve put Sharpie marks on the deck for each of my vehicles. Like Mac’s gear, the Weigh-Safe isn’t the cheapest product on the shelf, but the time saved, improved handling, and peace of mind is priceless.

The third style is the weight distribution hitch, or anti-sway bars, which are common on heavy RV trailers, toy haulers, and so on. They incorporate triangulated bars linked from the mid-point on the trailer’s tongue to tensioning sockets on receiver assembly. Their purpose is to distribute the load from the tongue and ball through the receiver and across the tow vehicle’s chassis. The result is much more stable handling.

Hitches, trailers, and cargo are expensive, and keeping the dirtbags at bay when we park is always a concern. From receiver pins to coupler clamps, Bolt Lock offers an extensive line of products designed to keep sticky fingers from driving away with your stuff. Crafted from hardened stainless steel, they feature weatherproof double ball bearing lock tumblers. And, you can configure all products to use your vehicle’s key. The Weigh-Safe system also offers a high-quality one-key system that includes coupler and receiver locks, but utilizes an Ace-style lock (radial tumbler).

TIP: Receiver and coupler locks are inexpensive insurance against theft.

I’ve never been big on dragging trailers into the backcountry, but tag-a-long abodes have become all the rage during the last few decades. The pintle and lunette ring has been around since C.G. Clement patented the design in 1919. Because the pintle can endure much greater receiver-to-trailer angles in technical terrain, they were standard issue on military vehicles beginning in WWII and continue to be used for hauling heavy equipment. But they are clanky and rattly, and a better mousetrap would soon replace them for overland use.

Since I’m not the expert on the subject, I reached out to Mario Donavan at AT Overland, one of the early adopters in the backcountry trailer genre. His go-to hitch is the Max Coupler, which is rated at 8,000 pounds (12,000 minimum breaking strength) and has a three-axis-point design that allows it to achieve nearly any angle of deflection.

TIP: An off-road trailer coupler should be able to achieve a spherical 180-degree deflection angle without binding.

When I purchased the Big Tex I jotted down a checklist of upgrades. This included sealing the wood deck, adding a storage box for straps, wheel chalks, and accessories, and installing a winch. The winch would require a dedicated battery, and that battery would require a means to keep it charged.

The deck was treated to Thompson’s timber oil, I sourced a weatherproof aluminum storage box on Amazon, and called Warn Industries for ideas on the winch. Based on the trailer’s 7,000-pound GVW and anticipated loads, they suggested their 5000 DC. Worst case scenario it will be used for pulling a dead (but rolling) vehicle up the ramps, so the 5k capacity should be appropriate. It will be powered by an Odyssey Extreme battery kept topped off by the low-amp 12-volt lead on the 7-pin connector. This should be fine for single pulls, but I may need to run a dedicated 4-gauge cable fitted with Anderson plugs directly to the truck’s battery at some point. The 5000 DC will be mounted on a Warn Jeep TJ winch cradle, but I will need to reinforce the trailer’s subframe to support it. I’ll also be upgrading the tires from the cheapo units that came on the trailer.

As I headed off to Moab on America’s Loneliest Road (Highway 50), I thought about Colin’s comment, “$30 big-box-store straps.” My CJ-7 is one of only five in existence, irreplaceable, and the source of many smiles when I get behind the wheel—which I’m sure is the case with your precious toys. When we hook them up to our tow rig and drive away, let’s ensure every link in the chain is worthy of safely ferrying them to their destination.

See you on the trail,

Chris

Conventional hitches are broken down into five

classes based on receiver size and load capacity.

Class I: 1.25-inch receiver, up to 2,000 lb.

Class II: 1.25-inch receiver, up to 3,500 lb.

Class III: 2-inch receiver, up to 8,000 lb.

Class IV: 2-inch receiver, up to 10,000 lb.

Class V: 2- to 2.50-inch receiver, up to 20,000 lb.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article appeared in TREAD July/August 2023.

Share Link