JASON MULLIGAN

.

May 26, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

JASON MULLIGAN

.

May 26, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

What drives men to push the limits of machinery to insane speeds, risking their safety and even their lives? Some say it’s the risk itself that raises their adrenaline. For many, it’s an intense drive to make their mark on history.

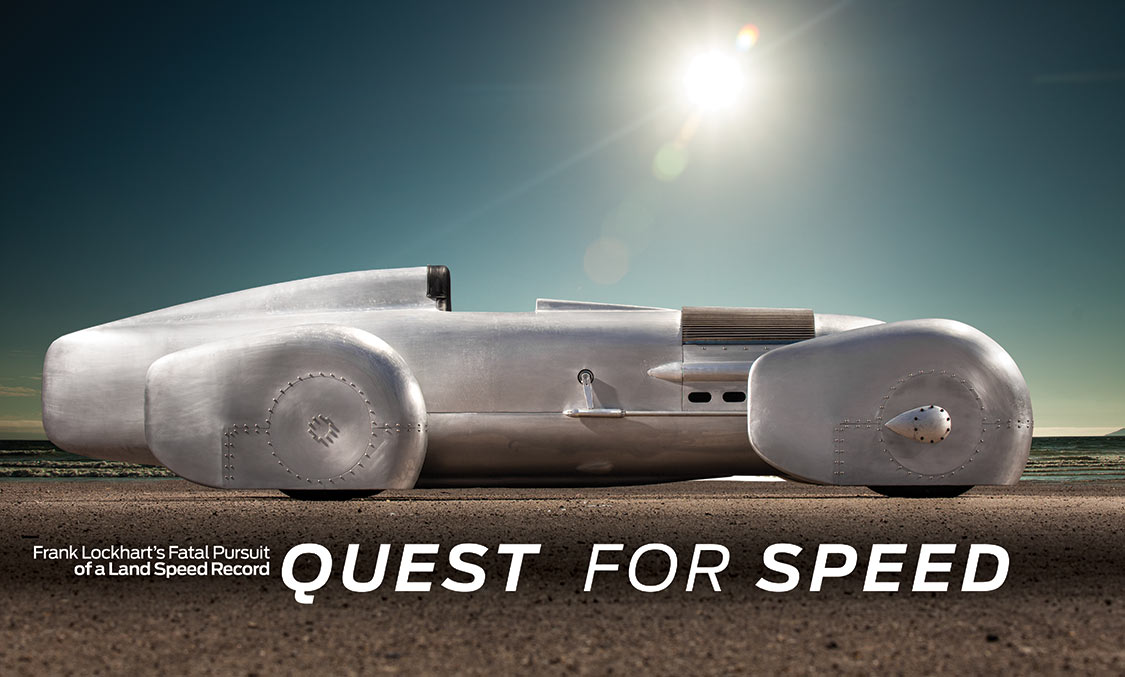

The tradition of pushing the envelope has guided a small team of builders to recreate some of the most important race cars of the past century. Their latest project is Frank Lockhart’s Stutz Black Hawk Special that was driven to set 200-plus mph land speed records in 1928. In the end both car and driver were lost to the gods of speed.

By the time his racing career was cut short at the very young age of 25, Frank Lockhart had already accomplished a great deal. Born in Dayton, Ohio, and raised in Southern California, he started out with dirt and board track. His big break came at the 1926 Indy 500 where he ran quicker lap times than the driver he was signed up to relieve, setting an unofficial track record. Starting twentieth, he moved into the lead by lap 72 and took home the win as a rookie in only his third year of racing; he was just 23. Lockhart won several more races and competed the following year at Indy with a supercharged and intercooled car, the first of its kind. He discovered that pressurizing the air heated it up, making it less dense; whereas cooling the air increased its density and created even more power. By the end of the race Lockhart broke a connecting rod but he’d also snagged first place. He set an opening lap-leader record that wouldn’t be broken for 64 years.

Allegedly, Lockhart was illiterate, but not only did he possess legendary driving skills, he had mechanical and engineering talents as well. He always pushed the limits when it came to racing, which often led to great starts and broken finishes come race time. But he saw solutions, such as intercooling the air for the supercharged engines to help produce more power and run more efficiently. It worked, and in the first test, the car ran 8.5 mph faster and helped him set a track record in Culver City, California. He soon took his car, with a single 91.5-ci supercharged Miller engine and minor modifications, to the Muroc Dry Lake Bed and clocked a record-breaking 171.02-mph run through the mile section of the oval track. However, it wasn’t an averaged run of a full measured mile, so it wasn’t an official land speed record at the time. Soon, large streamliners with powerful engines would hit the 200-mph mark with Lockhart nipping at their heels.

The first recorded land speed record was by Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat in 1898 with an electric-powered car running just shy of 60 mph. William Vanderbilt would set the record for an internal combustion engine at 76.08 mph to be beaten by Henry Ford in 1904, clocking over 91.37 mph in the measured mile.

The international battle for the top land speed record would play out prior to Lockhart’s attempts. Previously, a majority of the records were accomplished in the UK, with Malcolm Campbell pushing his Sunbeam 350 hp up to 174.88 mph in early 1928. Major Segrave sought to bring the record to the U.S. and ran at Daytona Beach, setting the record as the first car to not only reach 200 mph, but to reach 203.79 mph as well, besting Campbell’s record by a whopping 29 mph. The race was on as Campbell fought back in the Bluebird, quickly increasing the record by 3 mph.

Runs on Daytona Beach were taken at high tide right next to the breakwater to ensure the smoothest and most compact surface. There were inherent obstacles running at Daytona Beach, the unpredictable sand, surf and bumps throughout made for rough runs, and wind and unpredictable weather created difficult conditions.

The Black Hawk Special was a different animal than the current record holders of the time that favored heavy bodies with large and powerful engines. Lockhart opted for aerodynamics and a much smaller engine package to keep the car lightweight, and it held its own against the big boys.

Many firsts were accomplished during the car’s build. It was designed with the aid of a wind tunnel, and wheel spats were used to keep the open wheels from wobbling at speed. These spats turned with the wheels, causing sluggish steering while maintaining stability. The car had a wheelbase of only 112 inches, comparable to midsized cars of the future from Ford Deuces to GM’s A-body platform and what would become a standard for Stock Car racing.

Lockhart attempted to set a record in the 2-3L (122-183-ci) class at Daytona Beach and almost reached the top speed of the most serious competitors on the sand. With a set of two 91-ci (1.5L) DOHC supercharged inline-eight Miller engines, the Black Hawk Special was the smallest-displacement car to attempt the land speed record and reach 200 mph. The body was designed around Lockhart’s tiny 5-foot 3-inch, 135-pound frame and the engines were run in parallel on a common crankcase to keep the footprint narrow. The power-to-weight ratio would prove to be be key because the then-current record holder weighed 8,000 pounds but produced more than 1,000 hp. The Stutz weighed only 2,800 pounds but produced 570 horses at 8,100 rpm.

The only concern was whether or not the tires could handle the tested wind tunnel speed of 225 mph. Lockhart ran a set of Firestone tires that had been used on several land speed record attempts. However, Dickinson Tires put up a new but unproven set of tires for sponsorship. To test what would happen if a tire blew at speed, the crew fired a shotgun at the tire while it was running at 225 mph, and the vibration tore the tire machine to pieces. Needless to say, the risk of a tire blowout was great, and the aftermath would be catastrophic.

Stutz had always striven for speed, debuting at the Indy 500 back in 1911. The company had racers pushing for records since achieving the fastest average speed over a 24-hour period that averaged 68 mph. At the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1928, a Stutz racer finished second, which would be the highest standing for an American car until 1966. All of this was leading up to Frank attempts at the land speed record.

In late 1927, Stutz was looking to make a name for itself and Frank needed the funding necessary to chase the land speed record. A deal was struck and Fred Moscovics of Stutz, along with a few of his acquaintances, put up $35,000 (nearly $500,000 by today’s reckoning). Moscovics also gave him the use of the Stutz shops. To fulfill the sponsorship, the land speed car would include the signage “Stutz Black Hawk Special – Made in Indianapolis” along its side. The Stutz Motor Company Black Hawk production car would hit dealerships the following year as a less powerful and more inexpensive counterpart to the Stutz cars. It wouldn’t last much longer as the Great Depression took hold, and it was discontinued in 1930 with the Stutz company itself folding in 1935.

On April 25, 1928, Frank was settling into the streamliner as the race’s promoter, Joe Dawson, poured ice into a special tank to help cool the engines: In order to reduce drag a radiator hadn’t been installed. The Speed Meet was set up to showcase the Bluebird, Triplex and the runt of the group, the Black Hawk Special.

Lockhart had made a first pass with a run registered at 193.1 mph, then he pushed it further to clock a 203.45-mph run in the measured mile. This average of 198.29 mph fell short of the 207.552-mph mark set by Ray Keech in the massive Triplex Special that consisted of three 27L Liberty aero-engines for a total of 4,178 ci, compared to the total 182 ci in the Black Hawk, which demonstrates how close the Black Hawk came to the record with a much less powerful package, thanks to innovations like a lightweight design and efficient aerodynamics designed in a wind tunnel. It set the record by a large margin in the 3L class, but Lockhart wanted an overall land speed record win.

thanks to innovations like a lightweight design and efficient aerodynamics designed in a wind tunnel, It set the record by a large margin in the 3L class, but Lockhart wanted an overall land speed record win.”

On the next pass, in an attempt to increase the average run coming off the 203.45 mph pass, Lockhart pushed it even further. The Black Hawk Special cut a tire, likely on a sharp seashell. A similar occurrence happened at a previous Speed Meet where Campbell, and then Keech, set the record. Lockhart walked away with only minor scratches then because he only hit the surf. This time, though, the outcome would be markedly different. The tire blew, sending the car into a long skid before it went into a violent tumble, throwing Lockhart nearly 50 feet from the car. He was killed instantly.

The Black Hawk Special helped to show that lighter and streamlined cars featuring technological innovations were the wave of the future, outperforming massive freight train-style cars when it came to speed.

The Golden Arrow would take the record from Keech a year later in 1929. Segrave raced the Arrow to 231.45 mph at Daytona. He’d been the first man to hit the 200-mph mark two years earlier. The streamliner took aerodynamics to the next level because it was the first to feature a pointed nose and tight cowling. After that record was set, Lee Bible attempted to beat Segrave in the White Triplex that tragically crashed, killing him and a photographer. As a result, Segrave left land speed racing to venture into water speed racing, only to be killed attempting the water speed record the following year.

As speed record attempts rose into the 300-mph territory, the event was moved to the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1935 to allow for more open and predictable land to attain higher speeds with greater safety. Regulations for fire-resistant race suits, helmets, roll cages and other safety specs soon followed in light of the increased danger.

The current outright land speed record sits at 763.343 mph set by Andy Green in the ThrustSSC. The twin turbofan jet-propelled streamliner is also the first supersonic car. The record for an internal-combustion engine, wheel-driven car stands at 403.10 mph set by Donald Campbell in the Bluebird CN7 back in 1964. Initial controversy rose over jet-powered streamliners because they didn’t drive the wheels themselves. Later, the FIA combined the classes for the outright land speed record attempts. From that point on, jet power has been used to push land speed records to the next level.

While many veteran cars and streamliners of world record attempts have found their way into museums and car collections, the Black Hawk Special lay in wreckage at Daytona Beach. Spectators eager to get their own piece of automotive history grabbed up many of the pieces and parts. The twin Miller engines were scavenged and used in the Sampson 16 Special at Indy, among others. A few years ago, Jim Lattin began an accurate and running recreation of the Black Hawk Special.

Jim and his friends Rick Peterson, Bill Lattin and Santos Garcia had already recreated several crashed historic race cars, including the Stu Hilborn and Danny Sakai dry lake racers. As the team sat around one day, having a few beers, they got the wild idea to build a car that likely no one living had ever seen in person, the Black Hawk. They picked the car because of its history and innovations in body and technological design. The crew started assembling the chassis and suspension as well as the engine. Then it came time to build the unique body.

They started with a set of original drawings and a few photographs. They blew the drawings up to actual size, and soon discovered that there were some minor differences. It turned out that there were actually two bodies for the Black Hawk that didn’t match. The second and final body was crafted in the short months following Lockhart’s first crash at Daytona Beach and was completely destroyed on that fatal run.

The crew used the drawings to get the correct dimensions, and then made the parts following the photographs as closely as possible. Doug Kershaw even produced sets of wooden bucks based on the photographs and drawings. The bucks were handed over to Jeb Scolman of Jeb’s Metal & Speed who handcrafted all of the aluminum body panels. Rick streamlined some of the unique items, like the link bars, to stay true to the original design. For the special intercooler and ice tank, Ed Davis was brought in to painstakingly make functioning stainless steel vents.

The tribute car recreates the original Black Hawk Special, sans the twin engine. A Miller 91 inline-eight-cylinder engine was used for practical reasons while still remaining true to the heritage of the race car. Parts weren’t easy to come by, of course, but that wasn’t the only challenge. The unique steering setup, which used Schroder gearboxes, took plenty of expertise to build. The end result is an extremely accurate recreation of one of the most definitive race cars of its time. The car and driver never realized their full potential, but thankfully, their memory and legacy live on in the recreation, allowing future generations of hot rodders to see one of the cars that pioneered the land speed dream.

The end result is an extremely accurate recreation of one of the most definitive race cars of its time. ”

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link