Bill Senefsky

.

May 23, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Bill Senefsky

.

May 23, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Studebaker Corporation came out of the Second World War in remarkable shape. Like others in the automotive business at the time, it’d been forced to curtail civilian product production in early 1942 for an unknown duration. Unlike the other independent automakers, however, the company displayed advanced styling across its lineup for the auto-hungry nation in the post-war years.

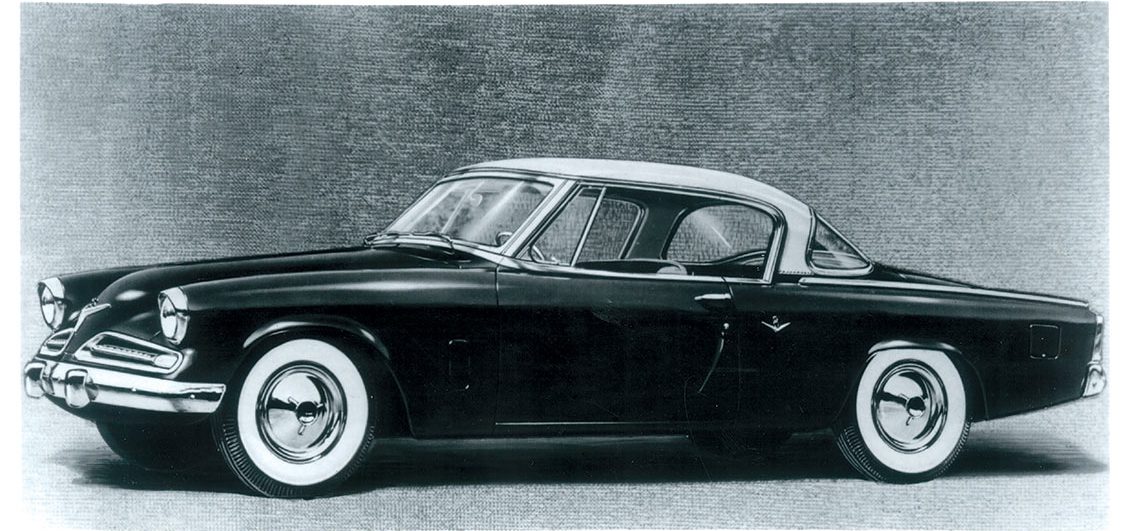

The continued relationship with renowned industrial designer Raymond Loewy lead the modern and futuristic thrust into the ’50s. Although his strong styling cues were seen on immediate 1947 post-war models, his radical stunner was launched in 1953. The first all-new profiled Studebakers certainly surprised the industry and are immediately recognizable to this day. The new styling was carried throughout the lineup, but the hardtops and coupes outsold the sedan platforms by a cool 4-to-1 margin. These new Loewy coupes were recognized as some of the most beautiful ever designed, and were later extremely popular with the hot rod and Bonneville crowd. These pioneers were kept in Studebaker’s lineup for years, in varying configurations, as the Hawk brand.

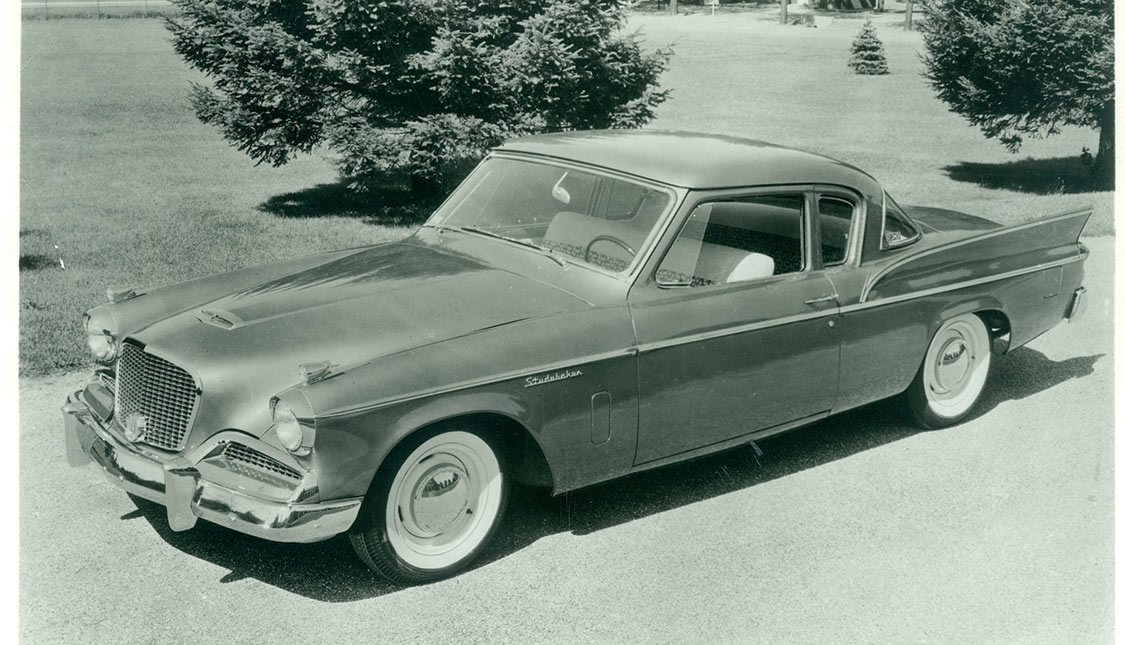

Studebaker’s four-model Hawk series was launched in 1956, in either pillared two-door sedans or hardtop configurations. Dubbed Flight Hawk or Power Hawk for the post models, the glass versions carried Sky Hawk or Golden Hawk labels. Flight Hawk versions were powered by the company’s Champion 185-ci inline six developing 101 hp. Power Hawk versions got the Commander 259-ci ohv V-8 (4.2L) developing 180 hp. A plainer Silver Hawk version was also produced, but not initially. All of the coupe versions shared their heritage with Studebaker’s wildly successful Lowey-designed 1953 Starlight series. The company continued to manufacture Studebaker Hawk versions through 1961, though the Gran Turismo version lasted until 1965.

The Silver Hawk nameplate replaced both the earlier Flight and Power Hawk versions in 1957. The Champion inline mill was a carryover but its President V-8 was enlarged to 289 ci (4.7L) developing 210 hp with the two-barrel and 225 hp with a single quad and dual exhausts. As a matter of interest, the Commander mill was only offered on export models.

Unsurprisingly, the Silver was the bread-and-butter version being plainer in appearance than its higher optioned Golden Hawk cousin. Of further note was the absence of chrome trim and the addition of a variety of paint schemes, some of which were dealer applied. Obviously the Golden Hawk’s supercharged engine and gold exterior trim along with the detailed hood bulge set these platforms apart. The years 1957-58 were also the time of the Studebaker-Packard merger, and thus the latter lead to a horrible sales year. In 1958, the Golden Hawk series was eliminated.

The year 1959 was a time of change for Studebaker. The compact Lark series was introduced and its sales successes lead the company to its best profitable year in half a decade. All of the company’s earlier models were eliminated now in favor of the Lark. The Hawk, thankfully, was saved by the dealer organization that continued to want both a high line and performance model.

Though the Silver Hawk platform was kept, several changes were introduced. Style-wise new tailfins were added with the Silver Hawk chrome script now mounted on the fins instead of the deck lid. “Studebaker” in individual block letters was now here, along with a new Hawk badge. Other changes included chrome moldings around the windows, a return from the 1953-54 models, and a change in the location of the parking lights from the front fenders to the side grilles. Some slight revamping of the interior trim was noted, as two former models of Hawk offerings were now one. The two-tone paint schemes were dropped except for special export orders.

Sadly, major changes were in store under the hood. The standard inline-six of the early ’50s displacing 169.6 ci was put back in service. This 2.8L mill developed 80 hp. The only V-8 choice was the venerable 259 (4.2L) developing 180 ponies with the two-barrel or 195 hp with the four. The 289 was dropped. Total Hawk sales reached 7,788 units.

After having a great sales year company wide, Studebaker found itself like the other independents and the Big Three facing major steel shortages due to a strike in 1960. Because of the lack of availability, the company focused on the successful Lark sales. Production of the Hawk was delayed until February 1960 when Lark sales began to fall.

Some industry analysts believed that Hawk witnessed a near-death experience due to the production delay and lack of marketing of the brand during this period. In any case, when production was resumed, the platform sported the return of the 289-ci (4.7L) mill. This power plant was now the only version offered for domestic sales. The inline-six and 259 V-8s were labeled for export only. The Silver designation, the last of the mineral nameplates, was also dropped from the Hawk series.

The year 1961 was the last year for the finned Hawk platform, so a beige accent was added to the base of the fin design between the lower moldings for a cheap styling accent. Bucket seats were finally added to the interior along with a new interior trim package. But the big news for enthusiasts was the addition of Borg-Warner’s (BW) new T-10 four-speed floor-mounted transmission. This unit would go on to establish the beginnings of the muscle car era. For Studebaker, it was a fine addition to its automatic, which was also supplied by BW.

The company continued through 1961 with both product and management problems. The steel shortage aside, the product line, relying too much on the compact market, competed directly against the big three and American Motors. Issues related to the Packard merger, mainly financial, also dragged company profits. In 1961, the company sold only 14,000 units, less than half of the previous year.

Changes needed to be made and radical plans were necessary. Sherwood H. Egbert was grudgingly elected president of the firm. An outsider to the auto industry, his initial mandate was to diversify the company into other business activities to absorb Studebaker’s tax loss credits. Only 40 years old at the time of his appointment, he was executive vice president of McCulloch Corporation in Los Angeles with a solid work record of 14 years. The popular chainsaw and engine supercharger concern had its beginnings like many others in an obscure Quonset hut operation located at LAX. The company also produced outboard motors. McCulloch would become Paxton and part of Studebaker.

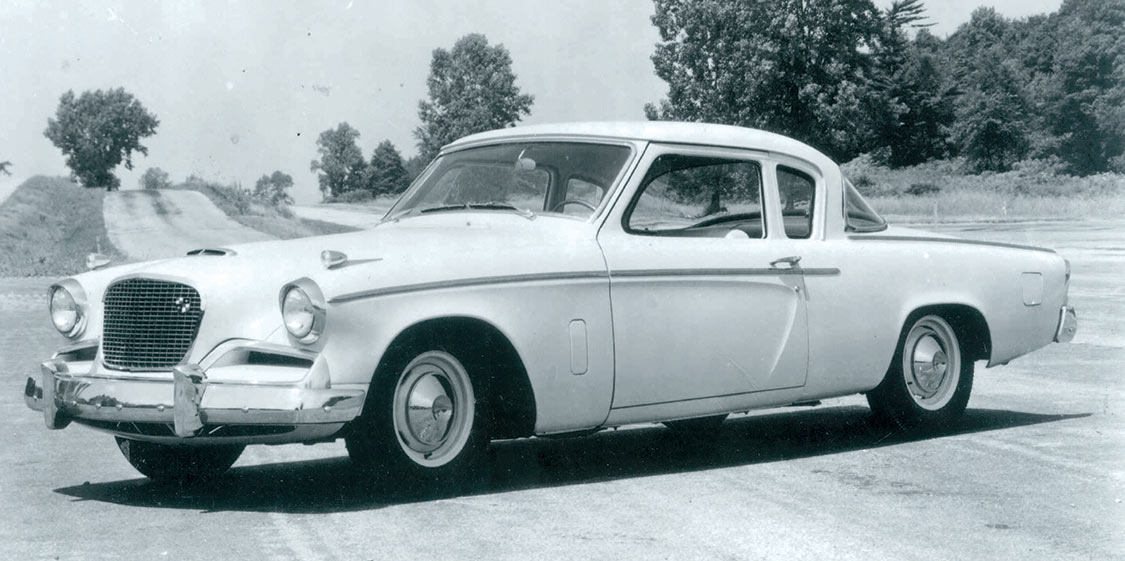

Upon his arrival to South Bend, he immediately boosted company morale by revamping the automotive division with the redesign of the Hawk series and the development of the Avanti. Egbert was a master of developing new product on shoestring budgets. Famed industrial designer Brooks Stevens was brought in to revive the Hawk, and Raymond Loewy and Associates developed the Avanti. Upon studying industry trends of the period, the new president felt there was continued developmental and marketing room for the ignored Studebaker Automotive Division.

Brooks Stevens was given the job of updating the Hawk brand. In reality, he did a masterful job considering the dated platform and mechanical restraints he had to work with. First and foremost, he gave the platform a European look with a more distinctive grille design patterned after Mercedes-Benz. In fact, Sherwood Egbert was in Germany during this period working on a deal to be the U.S. importer of the German brand.

“some industry analysts Believed that hawk Witnessed a near-death Experience…”

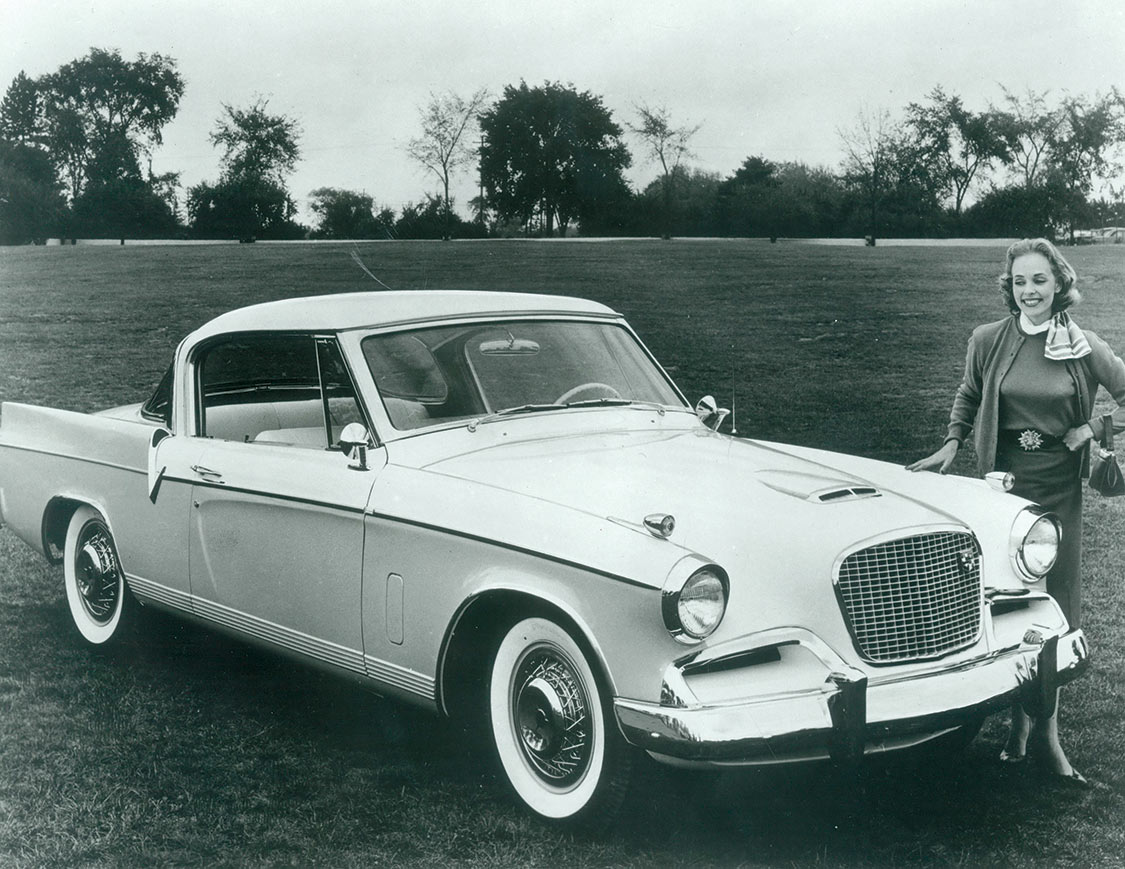

Other styling cues of the period were also used, including the obvious Thunderbird type formal roofline and the distinct lack of chrome trim. The hood received a slight bulge to create a subtle rounded effect. The rear deck lids were carryovers, but with a new overlay panel at the rear. The semi-wraparound taillight assemblies were new, allowing them to be seen from the side as well as directly from the rear. They also incorporated the back-up lights. New chrome trim was added on the top edge of the fender lines and along the lower body edges. Of particular interest was the rear window, which was now a flat piece of glass, though indented, which further saved production costs and added to the new look. The new roofline also was highly practical, adding valuable rear headroom to a previously unusable rear seat.

Several subtle and unique changes were carried out in the platform’s interior as well. Updated bucket seats were featured with a new console, which befitted the upgraded theme. A new dashboard cluster featuring aviation-style gauges could be ordered. A padded dash was an industry first. Cloth and vinyl or full vinyl-pleated trim packages were available. Unfortunately, though, first production runs of the popular pleated-vinyl option were of poor quality and slowed sales. The problem would be fixed with the ’63 versions offering superior Naugahyde vinyl materials now supplied by US Royal.

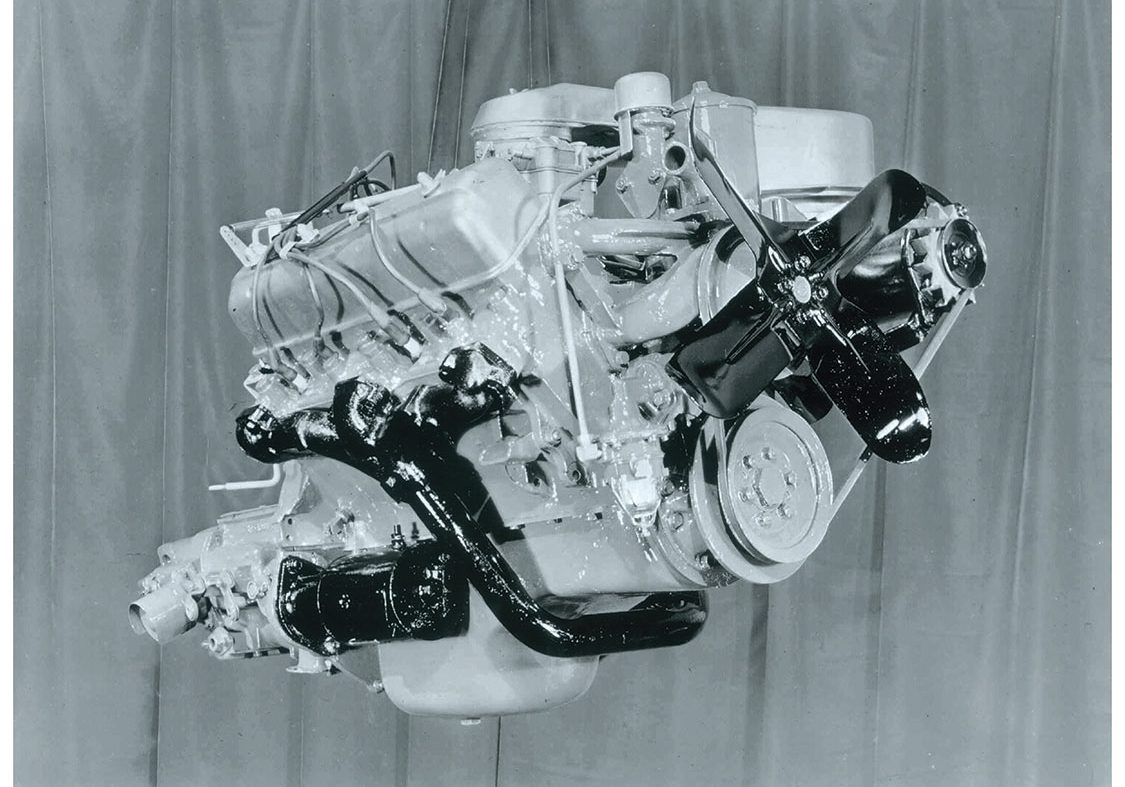

With regard to engineering, the platform underside was a clone of the original 1953 Lowey original. Sales prospects had a choice of two- or four-barreled versions of the company’s 289-ci (4.7L) V-8s developing 210 or 225 hp. A three-speed manual overdrive, four-speed (floor mounted) or Flight-O-Matic three-speed automatic was offered with BW supplying both. All in all it was a competitive package for 1962.

The 1963 versions could be ordered with the new Avanti-inspired Jet-Thrust R series eights, which could also be ordered throughout the entire Studebaker line. The R1 came with the naturally aspirated (read: quad carburetor) delivering 240 bhp. The Supercharged R2 (McCullough-Paxton) version developed 289 bhp (1 hp per ci). R3 versions were limited-production supercharged mills putting out 335 bhp from 304.5 ci. As expected, handling and braking tweaks included front and rear sway bars, radius rods at the rear and heavy-duty springs along with front disc brakes. A Super Hawk package equipped with either the R2 or R3 variant was introduced at mid-year. In any case, all of the factory performance goodies were also available separately at your local Studebaker dealer. Of further note, all factory-installed Avanti mills were coded “JT” for R1s and “JTS” for R2s in Hawks and Larks.

For the 1963 model year, slight refinements found their way into production. Style-wise, new front round parking lights replaced the earlier rectangular units. The side grille assemblies now featured a different mesh inlay. The same mesh pattern was carried over to the mail grille assembly. A new red, white and blue emblem was added to the Gran Turismo signage on the passenger doors. In the rear, the aluminum overlays on the rear deck lid were now reversed from the previous year. The red, white and blue theme was added to the rear Hawk emblem as well. Vinyl-pleating design and materials were changed, and superior vinyls with a vertical pleat pattern were used for longer wear.

More tooling money was finally available for the 1964 models. The first major item changed was the elimination of the carryover deck lid. The end of the fake rear grille was finally at hand. In place was a new smoother deck that incorporated a Studebaker Hawk script. Up front, another new grille insert was added, this time featuring a prominent Hawk emblem mounted in the center. The latest “Studebaker S” medallion graced the top of the grille collar.

Other features taken from the GT’s design sketches finally made their appearance. A half-vinyl roof accent, interestingly dubbed the Sport Roof, was added to the Hawk option list. Two colors were available: basic white or black. The material was applied on the roof’s front section over the front passengers and carried the modest price of $65. It should be noted that original GT renderings and prototypes featured a fully removable front roof section, for a full Landau effect. This unique option also didn’t make it to production due to the added engineering cost of further reinforcing the roof assembly. The half vinyl feature was it.

In keeping with low-cost industry trends, the interiors featured new vinyl headliner materials, another added upholstery choice, cloth and vinyl with silver thread, a new horizontal pleating design on the interior door trim, and a larger padded instrument panel. An additional lower padded dash was also added. A novel AM/FM radio was also offered from the factory for the first time. Continuing with the new corporate image, newly designed full-sized wheel covers were offered and shared with the rest of the automotive lineup.

Speed merchant Andy Granatelli had a close association with Sherwood Egbert from his supercharger days at McCulloch. Now a division of Studebaker, with Andy as its president, the time was ripe for reinforcing both Studebaker and Hawk’s performance image.

In September/October 1963, Granatelli’s Paxton division transported two production Gran Turismo Hawks to the famous Bonneville Salt Flats. Though part of a broad based corporate automotive brand effort, these sporty platforms performed flawlessly. Both were equipped with optional R series 304.5-ci mills. The R3-powered supercharged Hawk covered the flying kilometer with a speed of 157.29 mph. An R4, dual-quad carb setup-powered Hawk set the fastest average speed of 147.86 mph, highly impressive numbers for production-optioned automobiles.

Granatelli wasn’t finished though. October found Paxton’s team back on the salt with a top speed of 154 mph with the R3 Hawk and 135-plus with the R4. In all, Studebaker vehicles broke 72 USAC records that September, with an additional 337 added to the books the following October. These records formed the basis for the Super Lark and Hawk platforms of which few were produced, despite extensive advertising.

Studebaker ceased production of U.S.-made automotive platforms in December 1963. Obviously the sporty cars were the first to go. GT production numbers bore the stark realty: 9,335 units were delivered in 1962; a year later found the numbers reaching 4,634. By 1964, model sales declined to 1,767 units.

Bread-and-butter Lark series sedan’s equipped with Chevrolet’s mundane 283s purchased from GM allowed the company to last for another two years in Canada. These units were produced in Hamilton, Ontario. Today, all of these sites are but a memory, but the Hawk brand lives on with collectors and historians alike.

Share Link