Dan Burrill

.

August 17, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Dan Burrill

.

August 17, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

Marlo Treit has a fascination with speed. He also has a fascination with salt. Not the kind you eat, but the kind you race on. He has been involved with land speed racing for five decades. Before we get to the car, you should know that Marlo was inducted into the Dry Lakes Hall of Fame in September 2000, aligned with some of the greats of our time. In 2000, he was also inducted into the CARS elite group of contributors for the Portland Roadster Show in Portland, Oregon.

In his earlier years, he held motorcycle records, and since then has been involved with many record-breaking vehicles: streamliners, lakesters and roadsters to name a few. He is a man of many interests and talents, and all of them seem to involve speed. For example, a personal collection of some of his fast things includes a 1,700-mph Soviet MiG 21 aircraft and a Cessna 414 pressurized twin-engine personal transportation aircraft, and he maintains a salt flats lakester that holds current records.

He had the first lakester to ever exceed 312 mph in the quarter-mile at Bonneville and the first open-wheel car to exceed 333 mph in the mile. Innovation, rather than imitation, is the rule for this man. He has walked where no one has been and will continue to succeed using talents that have been honed by time. Visiting with him really is a trip through time and into the 21st century thanks to his many interesting and often amusing historical antidotes. Currently he is well into his latest obsession, Target 550. This vehicle may be the most exciting new car to invade the world of salt in the last several years.

“Starting with a clean sheet of paper, chalk on the floor and a reasonably open mind, we think we have constructed a vehicle that will exceed the speed that all conventional wheel-driven, piston-powered autos have attained to date by at least 100 miles per hour,” Marlo said.

That might seem to be a bold statement, but with Marlo’s history, the equipment available, a great crew willing to assist and current information received from the experts, it’s likely entirely valid.

Cashing in on his many years of experience, Marlo was quick to point out that money alone will not bring the program to the desired resolution. He went on to note that speed is the end result of good design, low coefficient of drag, proper power supplies, thousands of hours of construction, attention to detail and the ability to stay focused on the initial plan.

“This project was my vision, but after looking at the scope of it, I knew that I would need the assistance of others,” Marlo said. “I am now the coordinator, and for the most part, that’s the part I play in the whole scheme. This is where unsung heroes begin to add value to the program. Without able assistance from others, this is a project I would not be able to complete in my lifetime.”

Initially there has to be a person or persons who have vision. Without that, there is nothing. In projects such as Target 550, the vision is a minute part of the whole experience. In the vision one must assess the amount of compromise allowable, if any, in every aspect of the build. Driver safety, dependability of the engines, drive units, transmissions, tires, and last but not least, fire suppression and the redundant methods to arrest vehicle speed. These areas are where zero is the allowable compromise.

With that premise, the project commenced. When areas failed the sniff test, alternatives were immediately sought out. Many sources have been tapped to maintain the level of construction and design seen in the build diary.

Starting with a clean sheet of paper, chalk on the floor and a reasonably open mind, we think we have constructed a vehicle that will exceed the speed that all conventional wheel-driven, piston-powered autos have attained to date, by at least 100 miles per hour.

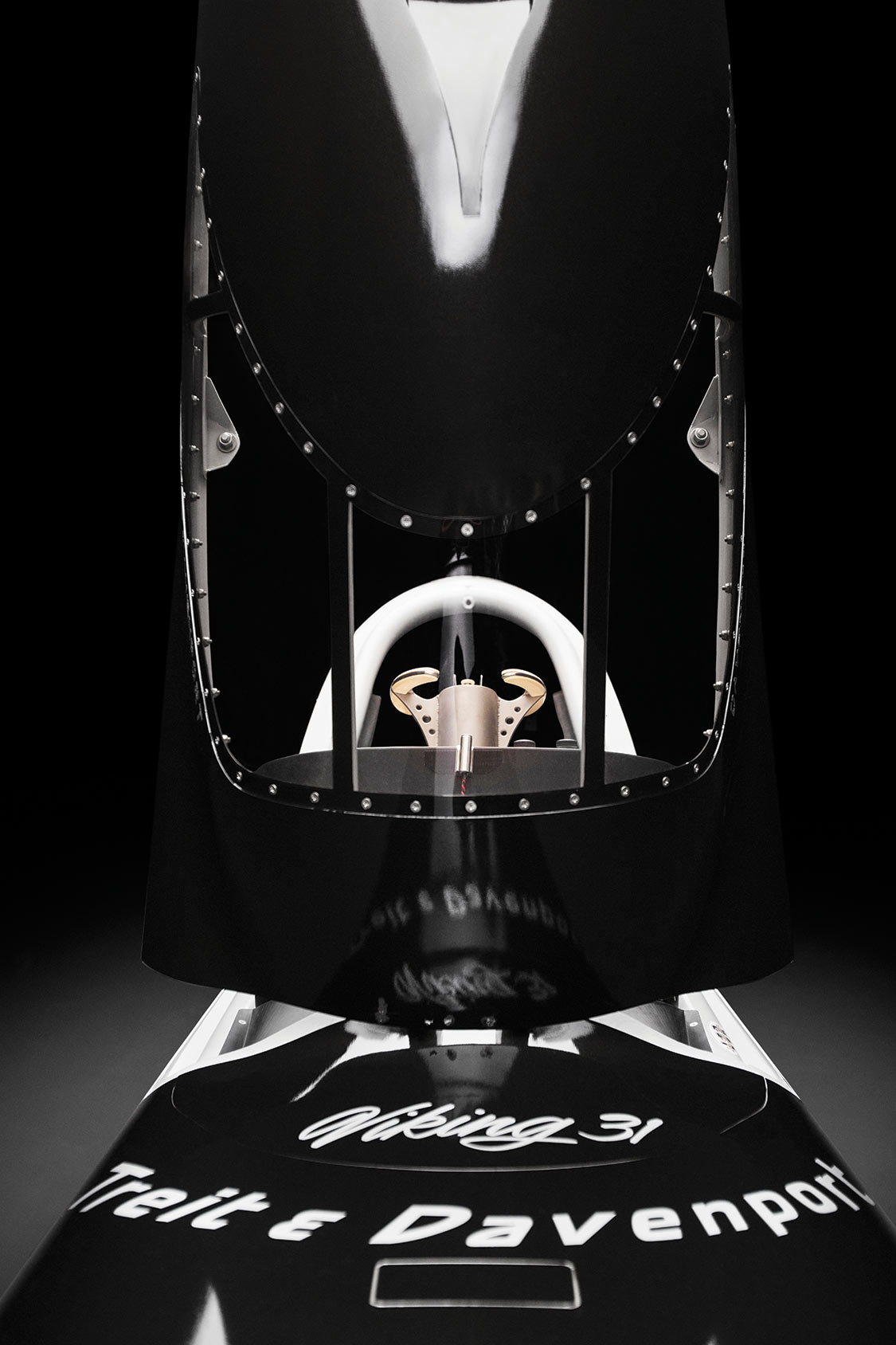

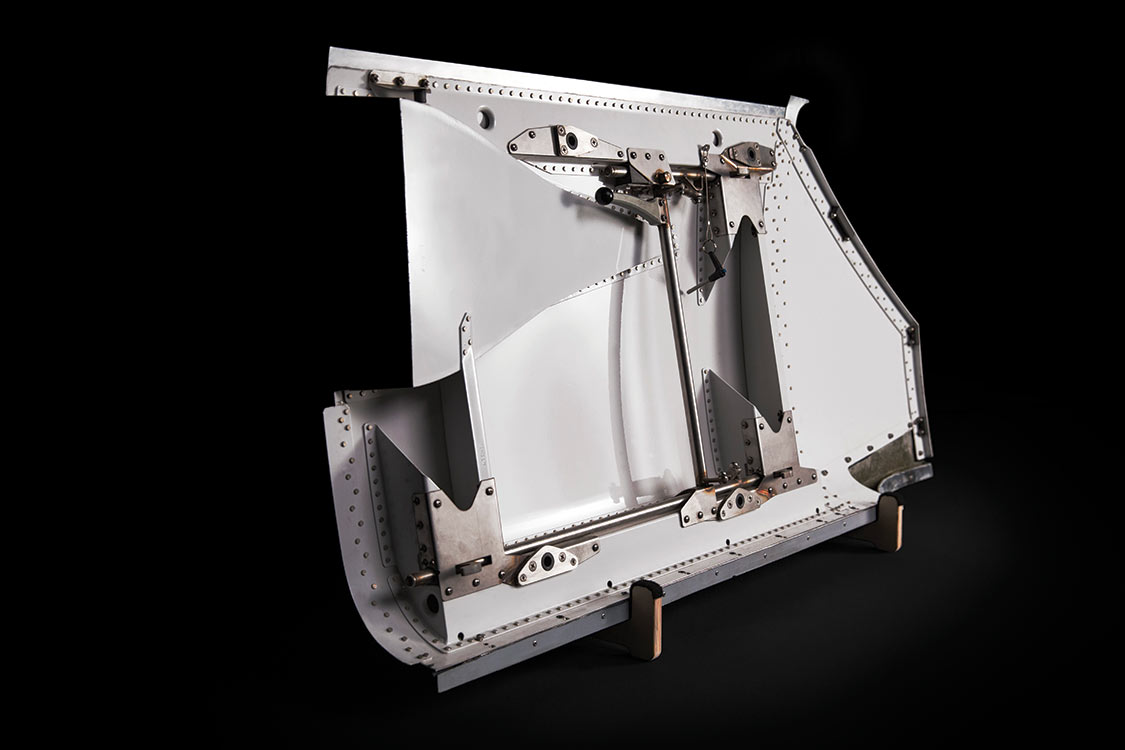

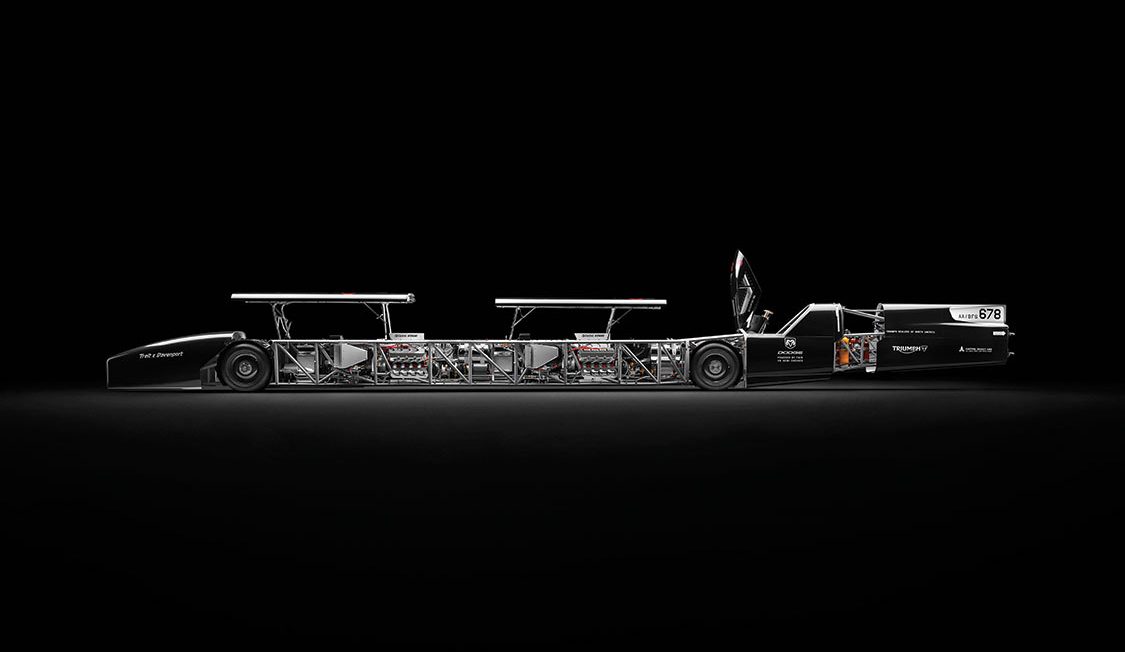

The car has a frontal area of 8.61 sq-ft and is 40-plus feet long with a 1.5-degree included angle on the sides of the body, front to rear. The model was tested and modified in the Western Washington University wind tunnel under the watchful eye of Dr. Seal, and the results were very satisfactory. Wind tunnel work has been a real learning curve. At this time, the front end has been reworked a number of times and the current front end tunnel adds 1,000 pounds of downforce when the front end is raised 4 inches in the air (which could happen if the car runs over a bump). The splitter that Jim Hume designed for the nose killed all lift and protruded around the nose by only 5⁄8 inch. “The staff thought that it should come back a little further on the sides, so we have installed the longer one for this coming test session,” Marlo told us.

He went on to say that outside of his shop he can account for 60,000 hours of work. In his shop he built the transmission, the differentials, all of the drive systems, the blower systems and the engines. Jim Hume did the tube work, sheet metal and latches.

“His [Jim’s] talents for chassis and body construction are without equal. Our conversation regarding this project was simple. Since I had been gathering parts for some time and he had done massive reconstruction on my lakester, he said, ‘I hear you want to build a new car.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ His next question was, ‘Have you commissioned anyone to do it?’ I replied, ‘No.’ Jim then said, ‘What will it be?’ My response was, “The fastest wheel-driven car in the world.

“Jim’s response, ‘I would be interested. Is there a budget or a time limit?’ I said, ‘No, we will know when it is done. How long it took and what it costs isn’t anyone’s business.’ From there on we made real progress,” Marlo said.

Work on the car started in 1998, and Marlo envisioned it would be a five-year project. Jim thought he was a little off on the projected timeframe. Twelve and a half years later, the car rolled out of the shop—it was 2012.

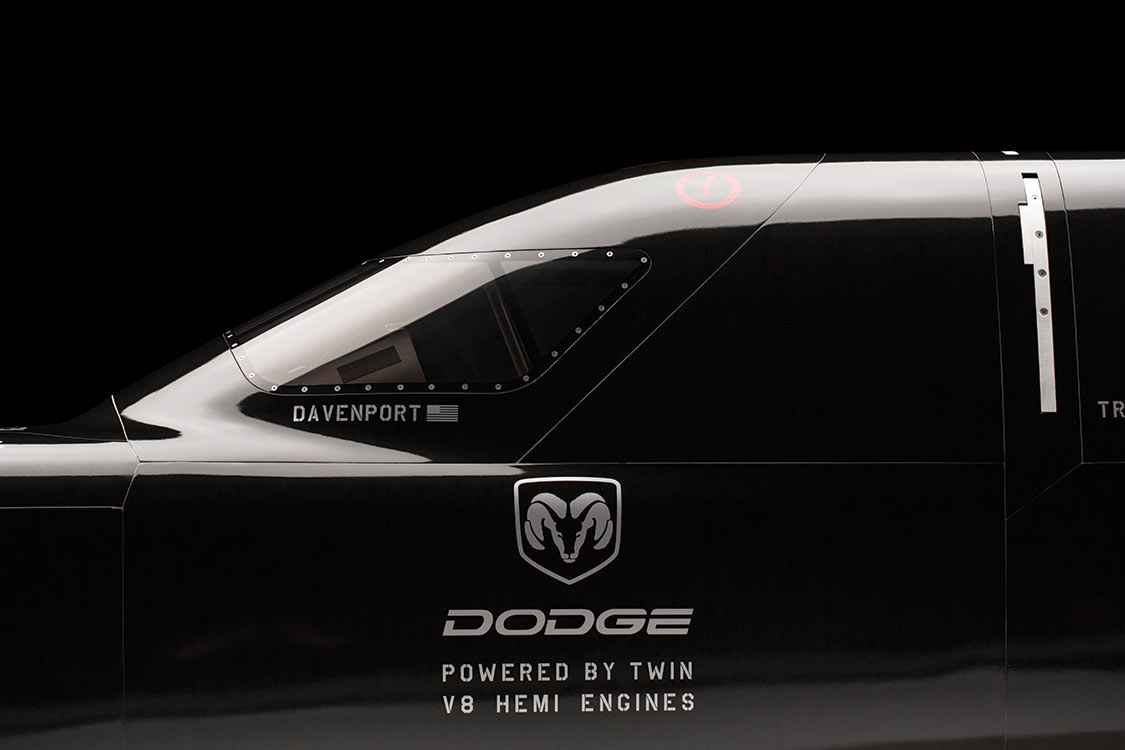

Marlo is a Ford guy, so this car originally was painted Ford Truck Blue and was on display at the Los Angeles Grand National Roadster Show in 2014. By chance, he received a visit from a guy who was hooked up with Triumph Motorcycles; Triumph of America sponsors a land speed, multi-engine streamliner. Marlo happened to know the builder, and he brought out the guy responsible for the Triumph program.

The Triumph executive looked at the car and noted that the company has had a disastrous test program. They had gone just 80 mph and almost burned their project to the ground.

“So I said to him, ‘You guys are going backwards at 80 miles an hour with a $1,000,000 piece of equipment,’” Marlo recounted. “In 1959 I ran 174 mph with a Triumph two-engine that I built in my garage over a period of six weeks. That’s when this guy’s eyes bugged out. He wanted to know where it was.”

Marlo explained that when he went into the service, he sold all of his stuff, so it was gone, but he did have some photos, which he showed the Triumph representative.

The rep asked, “Would you let us build a tribute? And if we do that and rewrap your car using the Triumph logos, and you take it to the Grand National Roadster Show, I will work on getting funding for you.” Afterwards, Marlo remarked, “What can I say, other than, okay?”

Canby Graphics, working with Triumph of America, put the package together and with only one week to go before the show opened, they got the job done and it looked great.

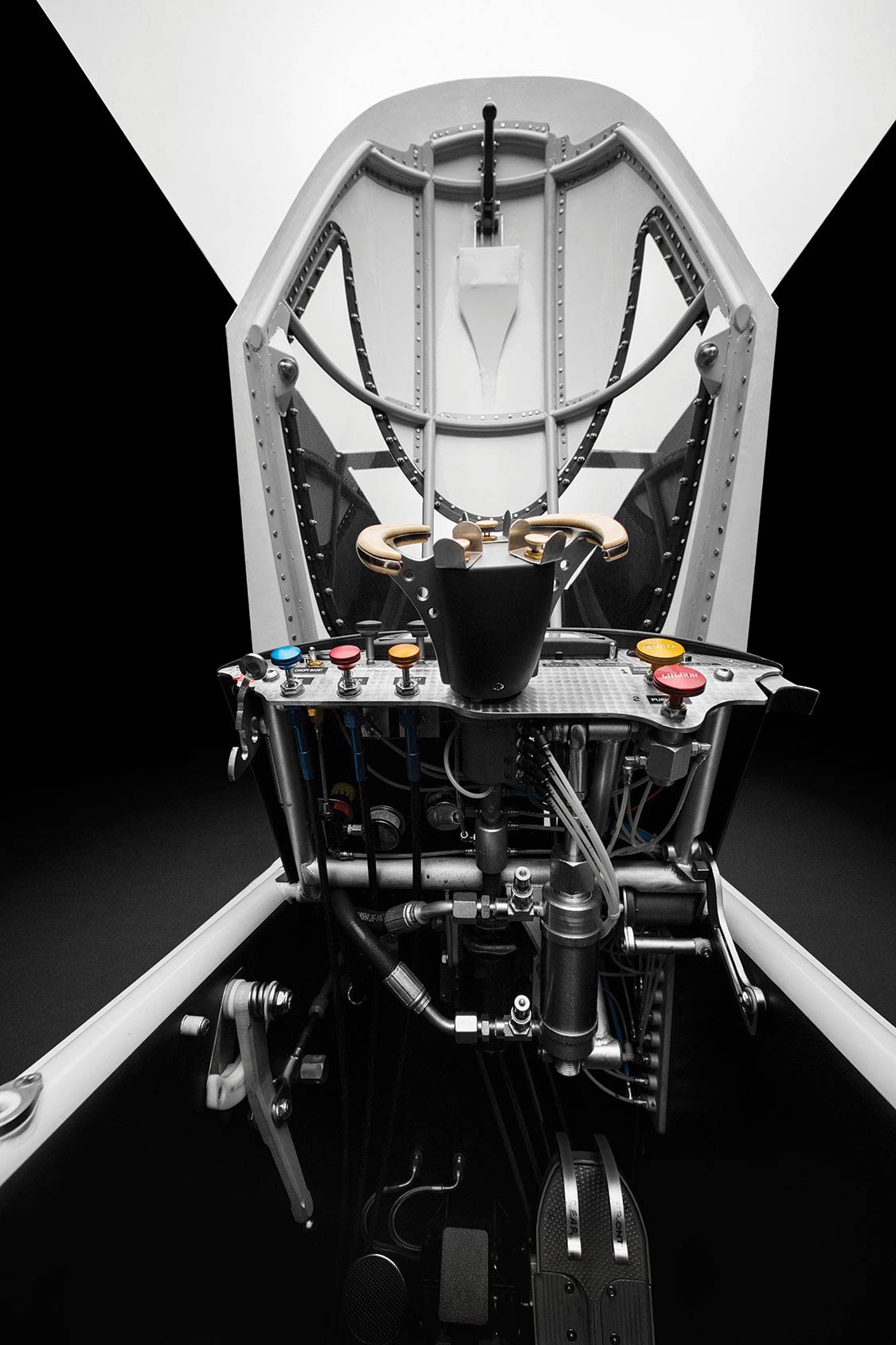

An interesting perspective on steering and brakes for cars of this type is to note that if you were going 100-mph down the highway, and you want to change lanes, how much do you steer the car? Do you actually move the steering wheel, or do you just “think” it? You basically just take the slack out of the linkage and you have changed the lane. Next, pull the emergency brake on just enough so that you can feel it, and between here and 10 miles up the freeway, you might get stopped before the rear brakes are on fire.

These land speed cars have no front brakes; they have rear brakes only. The only reason for the existence of these brakes is to stop the vehicle if you’re rolling in around the shop or moving it by hand.

“It’s got the best brakes that money can buy from Wilwood, the rotors are good for 7,000-rpm, and I would say the pads are good for about three seconds,” Marlo said.

That’s why the parachute systems on streamliners are mandatory. This car has four chutes, it has small brakes, and it has a set of speed brakes to help slow it down. “Keep in mind that the car weighs 8,000 pounds and it’s 43 feet long,” Marlo told us. “We intend to go 500 miles per hour with the car.”

The differentials started out as Halibrands used for Champ cars, and they are the last aluminum castings that Halibrand made while it was still in business. They were purchased for this car in 1992. Arrow Gears made the gears. The car has a 6-inch pinion and a 9-inch ring gear, so it has a 1.5:1 ring-and-pinion ratio. With the quickchange, it’s possible to get the ratio down to .75 or up to 3:1.

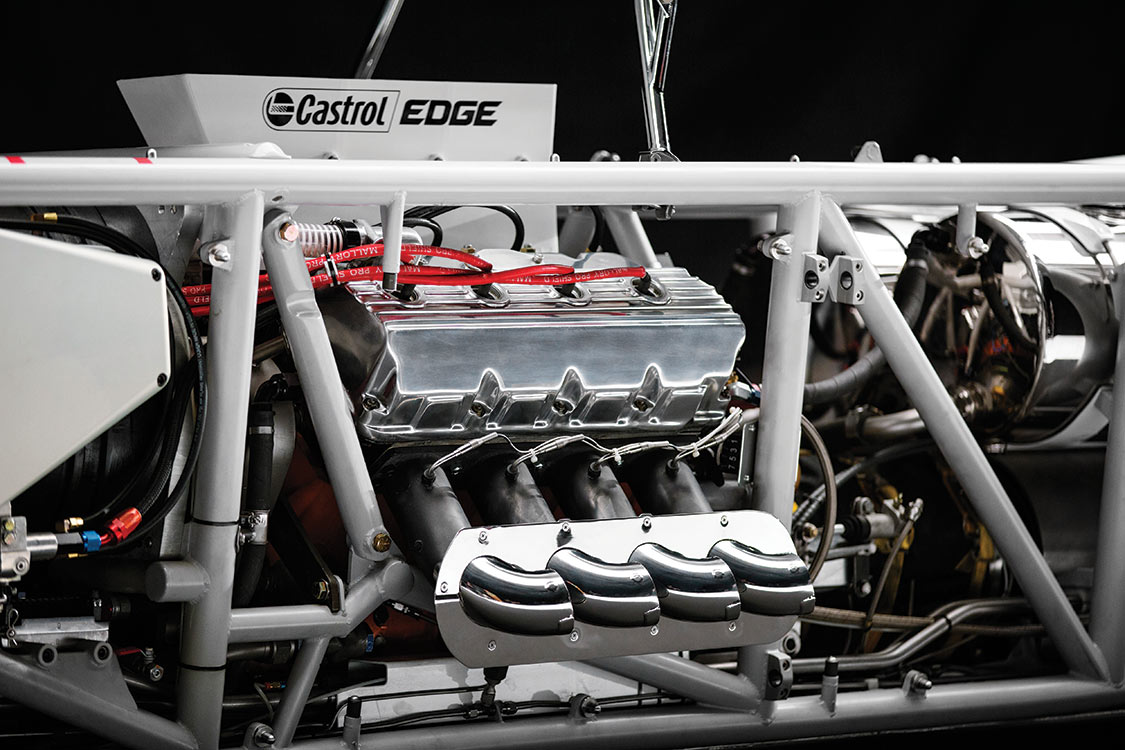

The car was tested at Woodburn Drag Strip in 2012, at Woodburn, Oregon. A set of stump gears was installed to make sure the tachometers and the other instruments worked, and the car went from 0-100 mph in 500 feet. Keep in mind, this vehicle weighs 8,000 pounds; it’s not a drag racer. The twin engines are 500-ci, late-model KB Hemis with Whipple superchargers.

“The second run that we had last year [2014], we had the most catastrophic failure that I could ever imagine,” Marlo remembered.

The Whipple superchargers have billet rotors. They are a screw blower, rather than an air beater blower like a Roots, so they are actually a real compressor. The rotors are billet magnesium. On drag race cars, the blower sits on top of the engine. For this application, the blowers are down in front of the engines to keep the height down so the driver can see. The front-engine blower somehow picked up a harmonic vibration.

When Whipples were made, they were made in Sweden, and the shafts that go into the rotors were pressed in from both ends. They are not one continuous shaft all the way though. They use a friction mechanism to time the rotors. For whatever reason, the blowers came out of time and they scrubbed each other, so there was a lot of powdered magnesium in the intake system. The magnesium went through the intake system and into the combustion chamber, where it ignited and then went out the exhaust. There was no problem with that except that these engines have a lot of overlap at the top of the exhaust cycle, and the magnesium was still on fire in the combustion chamber as the piston tracked back up through the intake stroke. The engine sneezed and blew a gasket out of the intake side. It happened so quickly the crew didn’t pick it up.

After the run, the crew checked the car and everything looked fine. Everything turned over well, so they went out and made another run. This time the sneeze was more noticeable, because the rotors were getting further out of time. The engine compartment from the water tank forward was filled with magnesium dust, and when it sneezed the next time, it blew off several body panels. These body panels are hooked on like the door of a safe, latched, ribbed and riveted. It takes a huge explosion to dislodge a panel. The force of the explosion ballooned the nose by 2 inches.

Les Davenport has been driving for Marlo since 1988. Les took on the task after Marlo destroyed his streamliner in spectacular fashion, and Marlo decided that if he were going to have another car, maybe he should also have a driver. Marlo built this car around Les, as a result.

At this point we didn’t have any superchargers because they were being rebuilt, so we put some port injectors on the engines, and we had no way to get good air to the engines, but the car will still run at 300 mph at 500 horsepower running alcohol.

Today, the car runs well. The crew went back in September of last year. “At this point we didn’t have any superchargers because they were being rebuilt, so we put some port injectors on the engines, and we had no way to get good air to the engines, but the car will still run at 300 mph at 500 horsepower running alcohol,” Marlo said.

With the superchargers, the engines develop 1,800 ft-lbs of torque each at 6,800 rpm. The ratio on the blower is 30% over and yields 33 pounds of boost. Five hundred miles per hour is within reach, and Target 550—well, that’s within sight, too.

Share Link