John L. Stein

.

June 01, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

John L. Stein

.

June 01, 2022

.

All Feature Vehicles

In all of American motorsports, there is no more hard-hitting, gut-wrenching, louder, quicker and dramatic event than drag racing. Everybody’s heard of the quarter mile, and musicians from Jan & Dean to Kenny Chesney have been writing it into song lyrics for a half-century. The mighty NHRA was founded on the simplicity of this 1320-ft. sprint over 60 years ago, and since then, drag racing’s influence on the development of muscle and performance cars has been incalculable.

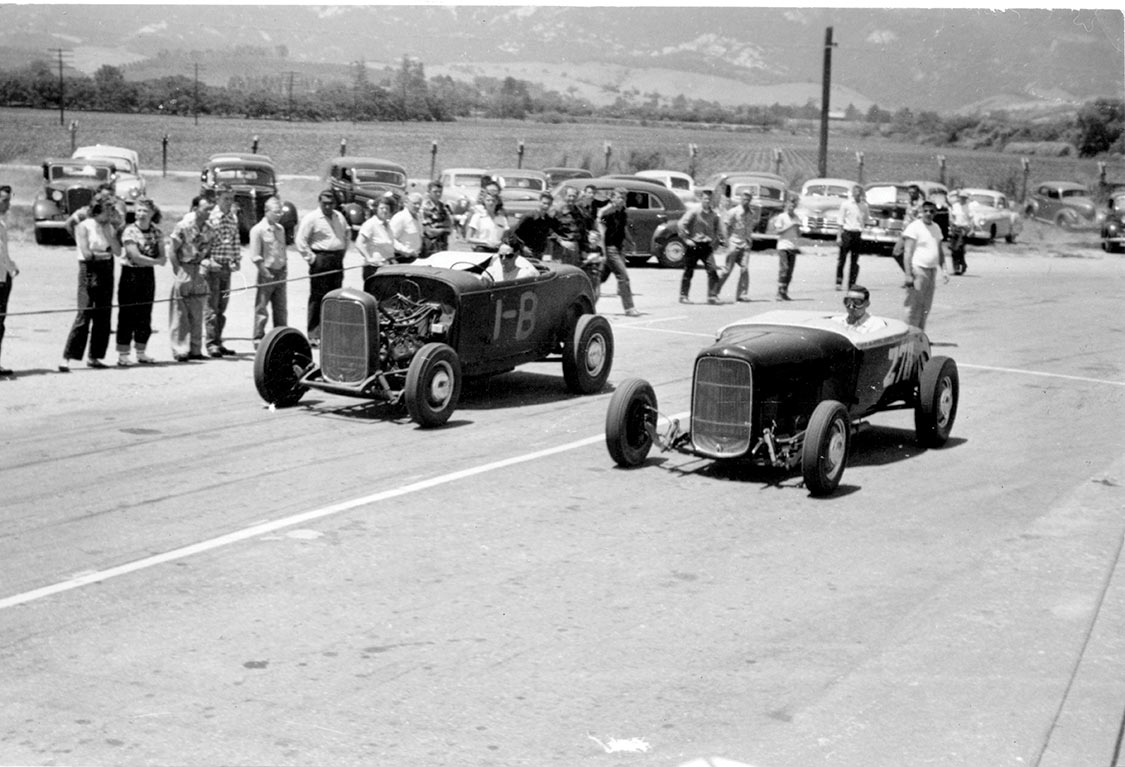

But where and when did organized quarter-mile drags begin, exactly? As it turns out, it was near the beach in little Goleta, California, in 1947. Local hot rodder Bob Joehnck was recently out of the service at the time. “After the war, there was a lot of street racing going on in Southern California,” he explains. “It came naturally for thousands of young men coming home, because they had several years to think about getting this Model A or that V-8 or whatever, and the first thing they’d want to know was, how fast will it go?

“We were tearing around, and a lot of us gravitated to running our cars at El Mirage Dry Lake in San Bernardino Country, California. I was 21 years old the first time I ran my roadster there in late 1946. I had a cloth helmet, some goggles and an old Army surplus seatbelt—that was it. The interest was so high, there were 51 cars just in my class. It was huge. They had a couple of sealed beams and pylons, and you’d go down there and just try to keep between them. Everyone wanted to say that they had gone 100 mph.

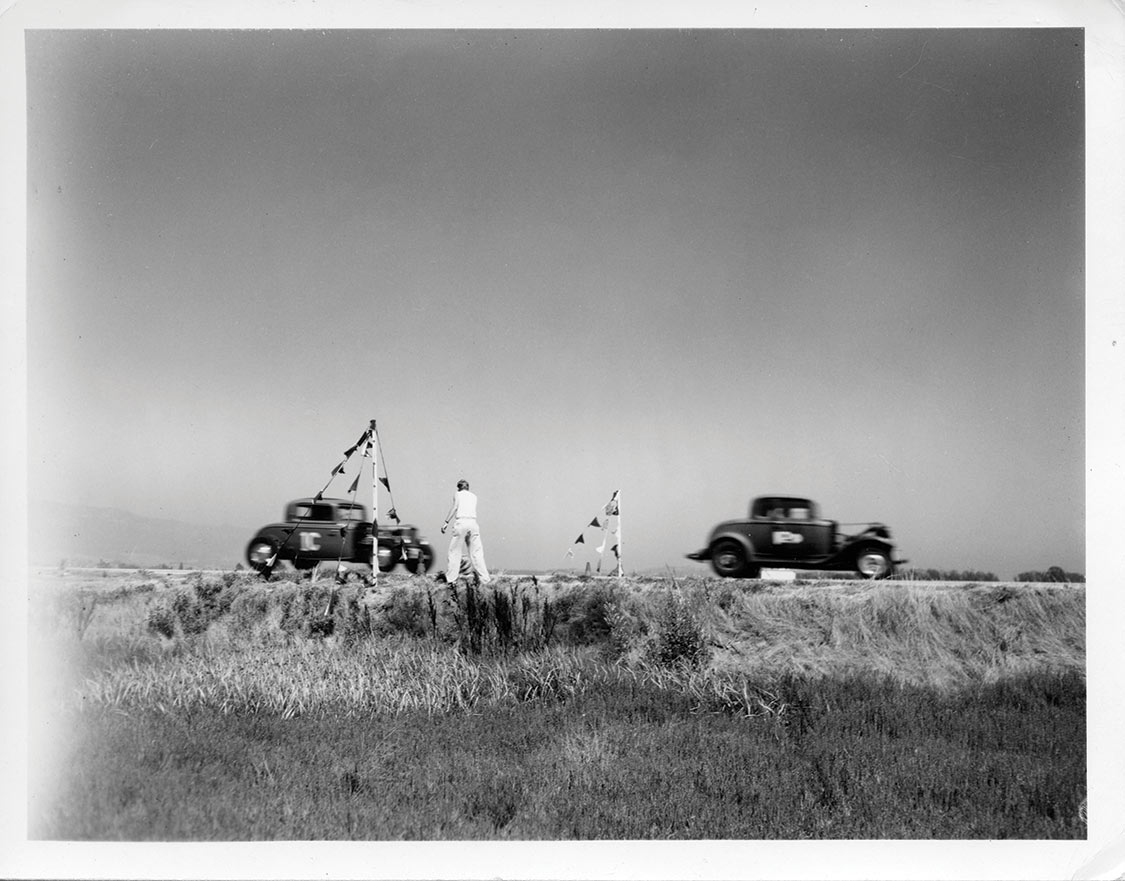

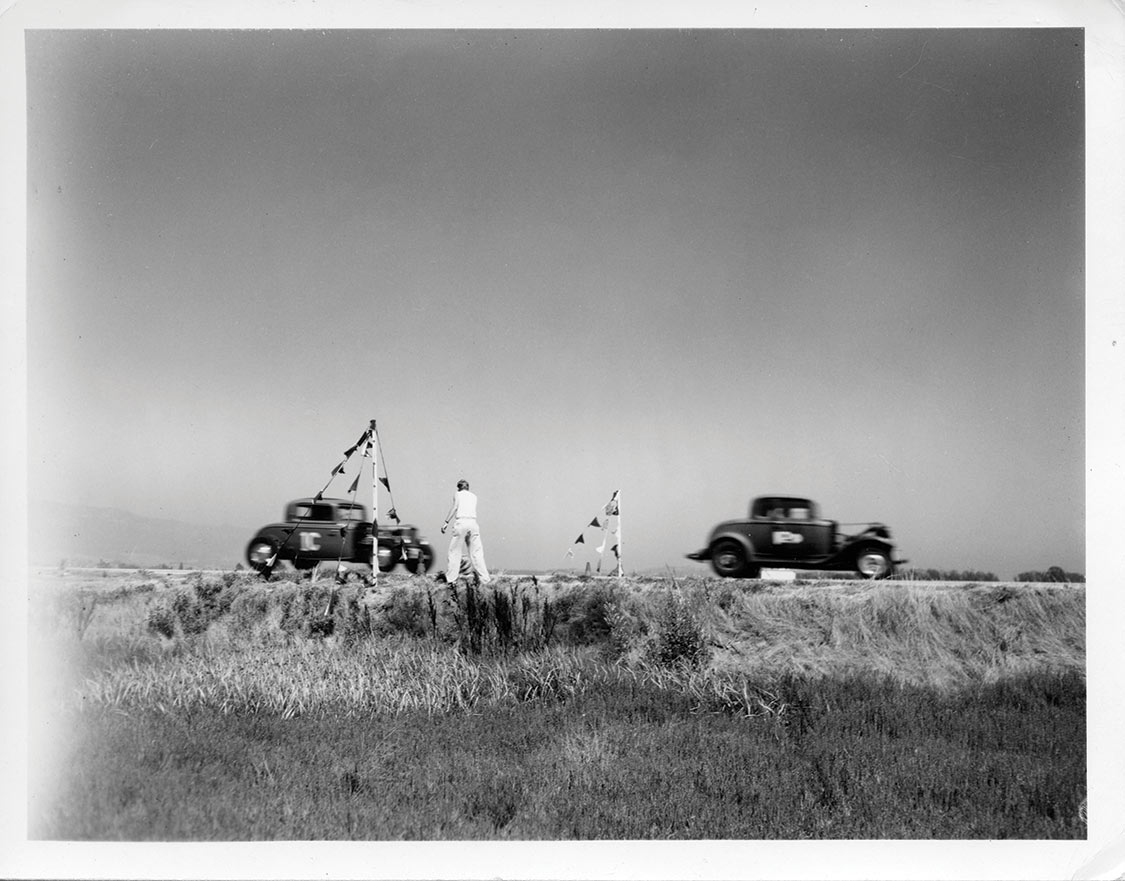

“There was one little straightaway there, just a narrow little 2-lane road on some lost land, and we decided we could race side by side there.”

“At the same time, a local group of us also used to go out to the municipal airport in Goleta. The west end of the airport used to be a Marine Corps Air Station, and there were a bunch of little revetments where they stored munitions. We used to go out there on Sunday and roar around the buildings one at a time. There was one little straightaway there, just a narrow little 2-lane road on some lost land, and we decided we could race side by side there. No one had adopted any standard length for acceleration runs—the distance was typically whatever the available road permitted.

“At the time there was a gentleman who was the airport manager. So we went to him and asked, ‘Can we go over there and run our cars?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I don’t see why not.’ Then he said to me, ‘Do you think you could get some kind of insurance?’

“I said, ‘Yeah, I think so. Let me try.’” So I went to a nice gentleman who was in the insurance business and told him what we wanted to do and asked if we could get some insurance. As I remember it was quite cheap, somewhere around $50 for the whole year, and it was with Lloyd’s of London. So in 1947, we formed this little thing called the Santa Barbara Acceleration Association. And that’s how it got started.

“We didn’t advertise it, we just went and did it. We didn’t have many classes, and there wasn’t much to it. We passed the hat so we could buy the trophies. There was no rent, and the insurance was next to nothing.”

I went to a nice gentleman who was in the insurance business and told him what we wanted to do and asked if we could get some insurance. As I remember it was quite cheap, somewhere around $50 for the whole year, and it was with Lloyd’s of London.

That explains the setup, but not the distance. “The reason why the drag-racing distance became a quarter mile is that a fellow came up from Disney Studios to write a little article,” Joehnck continues. “He liked cars and wanted to take some pictures. He interviewed me because I was kind of the ‘chief cook and bottle washer’ for the club. He said, ‘What do you do?’ And I said, ‘Well, we kind of come down here’—there was a start line with a flagman—‘and we take a rolling start and race down to that bridge.’ There was a bump at the bridge, and we could tell who won by seeing which car hit it first. And he asked, ‘Well, how far is that?’ I had to give him some dimension, so I said, ‘It’s a quarter mile.’ That was it. From then on we raced for a quarter mile.”

After staging the first organized drags, Joehnck spent a career building engines for drag, road, circle-track, land speed-record and boat racing, helping drivers such as Bob Bondurant make their names in the process. He also designed Edelbrock’s original 4-barrel high-rise intake manifold and built a highboy roadster that claimed B, C and D gas roadster records at the Bonneville Salt Flats, including a 227.336-mph record in 1991. Now 89 years young, Joehnck still goes to the shop every day.

John L. Stein is the Editor-in-Chief of Maximum Drive.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Visit our Cookie Policy for more info.

Notifications

Share Link